|

UPDATE! 09/11/2016

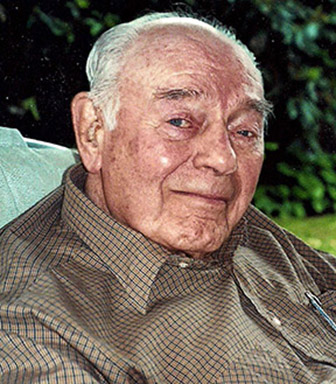

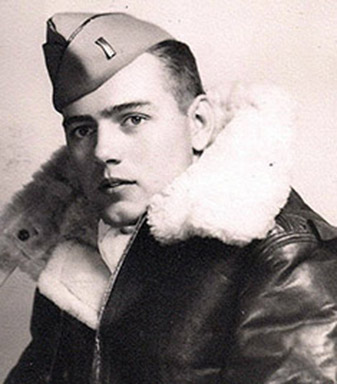

For the record, Jack Wendling became a commissioned officer and a B-24 co-pilot at age 18. Now 88, he still carries a current pilot's license tucked in his wallet."I have an old pilot friend," Wendling notes, "whose personal credo goes straight to the heart of the matter. Flying is not inherently dangerous. All it requires is your undivided attention." Evidence that Wendling himself pays homage to this aerial rule of thumb becomes crystal clear, as his narrative unfolds. Let's join our fledgling

aviator, as he spreads his wings for the first time.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ "In 1942 I was a 17-year old freshman at the University of Minnesota. The largest aeronautical school at that time. My dad took me for a spin in a twin-engine Curtis-Condor when I was five years old. From then on I was into it, building model airplanes and learning all I could about aviation. On a Sunday evening I happened to hear a radio newscast that said 17-year-olds could apply as aviation cadets. So I took the exam at Fort Snelling with a group of others, passing with the highest test score. I was then sworn in to the Enlisted Reserve Corps. I only got half way through the second quarter in college when they called me up in early April of forty-three. Then more physical tests at Nashville, Tennessee. Mostly eye-hand coordination to determine my reaction time. Walking wasn't allowed. Everything was double-time from the moment your feet hit the barracks floor at five-am. " I first flew in the Boeing PT-17. Or Stearman trainer, as they called it. With two open cockpits - the instructor sat up front, and the cadet behind. Dual controls. All the flight instructors were civilians. It was my good fortune that my primary instructor, "Smokey" Olson, was the best at his trade. Before getting in the airplane, he'd make certain I understood exactly what we were going to do. Once airborne,he would demonstrate that particular aerial maneuver a time or two, while at the same time describing his actions. Then I took over the controls to duplicate the maneuver, while Smokey helped talk me through it. Back on the ground, he would critique my progress. Each maneuver was practiced a number of times. Failure to 'get it right' within a given time frame meant flunking out of flight school. "Flying blind at night or in heavy cloud cover - without visible reference to the horizon and depending entirely on gyroscopic instrumentation--was another learning experience. You had to learn to place absolute trust and reliance on your instruments. Say you're sitting in a chair with your eyes closed. You know up from down, from the pressure on your butt. But in a cockpit, there's more than simple gravitational pull at play. Severe air turbulence can leave the false impression the aircraft is diving or climbing. Vision and inner-ear balance are no longer of value. What you 'feel' is wholly unnatural - an entirely new, unprecedented experience. So … making the sudden switch from a familiar two-dimensional world, to a strange three-dimensional world, had to be mastered. The challenge was to feel confident and comfortable in your new environment -- but ever alert. "Smokey Olson was a prime example

of someone who'd totally adapted. He'd been an aerobatic stunt pilot

in the thirties, performing at county fairs and giving rides. His specialty

was inverted landings. As in - upside down. Now, that's simply not possible.

You'll kill yourself and wreck the plane. But Smokey figured out how

to get around that. As he explained it to me, he rigged his bi-plane

with an extra pair of extended landing gear struts, so that the upper

wing surface on the bi-plane now sported a second pair of wheels, pointing

skyward. He also had an upside-down tail wheel attached to the tip of

his vertical stabilizer, so as not to damage the tip of the tail when

it made contact with the ground. And he'd land upside down and do a

delicate touch-and-go - then goose the throttle and get airborne again.

"Olson pulled it back to idle - dual controls, remember? "There was a split rail fence at the end of the cotton patch. I could see three men working in the field. Just as we passed over the fence, Smokey flipped the plane over and upright. If you'd been standing atop the split rail fence, you could have reached up and touched the rotating wing tip as it flipped over. Only then did he open the throttle and climb up, with a few feet to spare. "Olson and I stayed in touch -- casual correspondents. Smokey later transferred to a flying school in Louisiana. One day I got a letter from his wife. He'd taken a cadet up and the student apparently 'froze' at the controls. They were both killed"

"Then off to Albany, Georgia in preparation for advanced twin engine school. This time we flew Consolidated Vultee BT-13s, the next step up and a very important phase in the training cycle. We even did aerobatics in formation. With enough practice we could stick like glue to the instructor. On completion of this course, I was awarded my wings and second lieutenant bars. Before departure, I was approached with an offer to become a flight instructor. I said: 'Do you realize I'm just 18 years old?' A few days later I was informed they'd discussed it at command level and did some checking around…and found out that as far as they could determine, there wasn't any record of a commissioned eighteen year-old B-24 pilot younger than myself anywhere in the U.S. Army Air Corps. * "Then back to Montgomery and B-24 transition school. A lieutenant instructor gave myself and three other students a walk-through. He then asked if there were any questions. I said: 'How do I get out of here and into fighters?' And he said: 'You don't think you can fly this airplane?' And I said: 'I can fly the box it came in.' This wasn't brash bragging on my part, but rather an expression of self-confidence in common use at the time. What it meant was -- give me a pilot's information manual and some dual instruction, and I can fly anything you've got. My hope was that two-engine advanced training would lead to the P-38, a twin-engine fighter. Later, I kept bugging him about it, but I was wasting my breath."

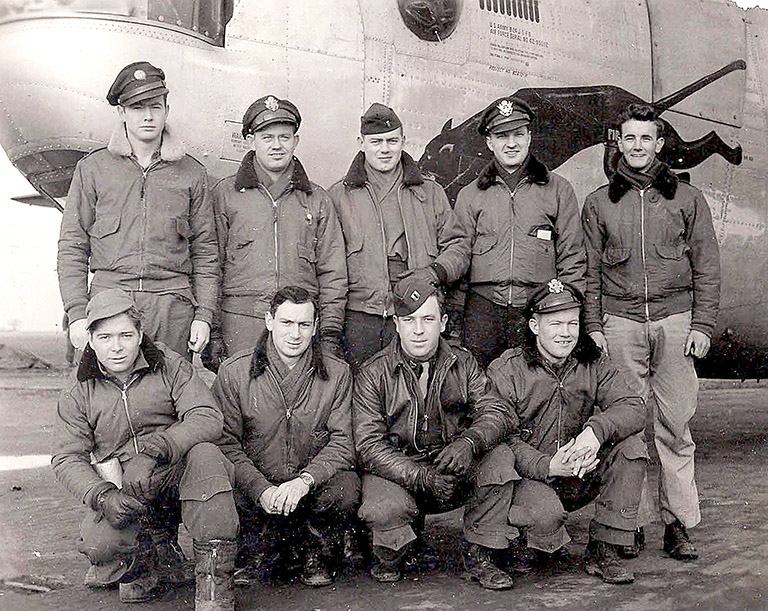

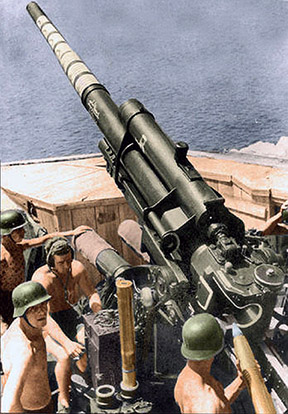

Jack waited for a crew to be assembled and further trained, then journeyed to Topeka to pick up a factory-fresh four-engine B-24. First a check ride, then off to England. Destination: Attlebridge Air Base, in the Midlands some 70 miles from London. Home of the Second Air Division, 96th Combat Wing, 446th Bomb Group. Jack's crew members relinquished their Liberator, never to see it again. "Most people think you get a plane, and you stick with it - it's yours until it's wrecked or shot down. Not so. Our crew manned at least six different B-24s for varying lengths of time. Just off-hand I recall the 'Ghost,' 'Ghost II,' 'Flying Red Horse,' 'Parson's Chariot' and 'Lady's Home Companion.' And I can't forget 'Black Cat.' She was the last 8th Air Force B-24 shot down over Europe, on April 21, 1945. Our crew flew 'Black Cat' on at least eight combat missions. You can read a book about her - 'Wings of Morning.' I talked with the author at a couple squadron reunions. Reassignments also happened with the aircrews. Over time, four of our original ten crew members transferred out for various reasons and were replaced. "Superstitions, we had them. Each man had to deal with bad luck in his own way. Keep harm at arm's length. For the past 68 years, I've always put my left shoe on first - without fail. I also carried a rabbit's foot on each of my 30 combat missions. The other guys might get slammed, but not me. Ever hear of 'lucky' clothes? Like lucky woolen underwear? Some guys wore their long johns year-round, on each and every combat mission. Some never cleaned them - that might wash away the good luck." Wendling flew his first bombing mission August 3, 1944 in company with 35 other Liberators. Scattered throughout the United Kingdom was a total of 46 such groups. Each group contained a minimum of 60 bombers, either B-17s or B-24s. The fighter groups, which escorted the bombers to their targets, were slightly greater in number. Wendling's crewmates in the squadron were the only crew to fly all their combat missions as the lead aircraft - the most dangerous position in a formation when it came to anti-aircraft fire. German flak batteries always attempted to focus on the element leader's plane whenever possible, because the bombardier on that aircraft determined the aiming/drop point for all the other B-24s in that flight. When the 8th Air Force increased the number of mandatory combat missions from 30 to 35, Jack and those crewmates who qualified were only required to complete 30 missions. As well, all of Wendling's missions were deep into Germany, a round trip averaging between six and eight hours. After takeoff, and barring bad weather, it took a good 45 minutes to assemble a formation at 10,000 feet--if all went well, that is. Bomb loads were customarily dropped from an elevation of 22-24,500 feet. In all, the 466th flew 5,693 sorties during 231 bombing missions and delivered 13,000 tons of explosives from March, 1944 to late April, 1945. The cost: forty-seven B-24 combat losses, 333 aircrew killed or missing in action, 171 POWs. As well, battle-scarred crew members could be found scattered throughout the squadrons. In all, 135,000 men flew in combat with the 8th Air Force; more than 26,000 perished and another 20,000-plus were wounded. Statistically, the 8th casualty count actually exceeded that of the entire U.S. Marine Corps. A total of 6,537 B-17s and B-24s were lost in combat, together with 3,337 fighter aircraft. "We had our share of surprises. Least expected was the trip when we lost oil pressure on the number three engine and had to abort the flight. The return course took us across the Zuider Zee and out over the English Channel. We still had our three-ton bomb load, stuffed with RDX. Per pound, the explosive power of these bombs was five times greater than TNT. "The bombardier suddenly called up and said he could see the silhouette of a submerged submarine. It was underway, and the sub's periscope was leaving a wake. The ocean surface was like glass - had the wind been blowing, we'd never have spotted it from our height at 8,000 feet. "I got out the maps and discovered we were over a section of the channel where Allied shipping was forbidden to enter - most likely because the Germans had planted charted minefields throughout the area. So we maneuvered the plane and carefully lined up on the sub's course. The bombardier let go the entire load of 500 pounders. Mind you -- not for nothing was our bombardier known as a master of his trade. He was close to getting his degree in physics when the war broke out, at which point he enlisted. Dropping bombs on target was just another ballistics problem to be solved, and he became very good at it. His salvo perfectly straddled the submarine on either side. Once the explosions subsided, we spotted a hump of boiling water surging to the surface. At debriefing, we told the intelligence people about it but we never heard anything back. I like to think the Germans had one more missing U-boat." An example of the Eighth's impressive display of air power occurred the day before Christmas, 1944. The maximum effort sent up a total of 2,017 B-17 and B-24 bombers, plus 1,700 fighter aircraft .Wendling and his crew were absent, however. No transportation. Their aircraft was in 'intensive care,' having suffered near-fatal wounds the day before, on December 23rd.

"The weather had finally cleared and it was a beautiful day. Our target was a large storage depot that was supplying the German ground forces during the Battle of the Bulge. Once again, we were the lead aircrew flying in 'Ghost II'. What we didn't know was that the Germans had several 88mm flak batteries parked in the vicinity, mounted on open flatbed railway cars. They seemed to be 'flock shooting' that day. We had thirty planes in the flight. None were shot down, but twenty-two were flak damaged. Compare that to an earlier trip to Ulm. You've heard the expression - 'an image burned in your brain?' The bomber off our left wing, maybe 200 yards away, took a direct hit in the bomb bay. Instantly there was a humongous ball of fire traveling horizontally across the sky - around fifteen hundred gallons of burning fuel. All that was visible was a wing tip sticking out of the flames. I carry that image to this day. "Just after our bombardier toggled his load, 'Ghost' tipped over on the left wing and spiraled down from 24,500 feet to 8,500 feet before we could wrestle her upright again. As we later figured it out, a full salvo from a gun battery of eighty-eights simultaneously entered our airspace. Three of the four shells connected. One went through the outboard portion of the right wing, clipping the aileron controls. A second eighty-eight went through the right horizontal stabilizer on the tail, which in turn took out the right rudder. The third round passed through the right wing behind the inboard engine. The first two shells didn't explode on contact, but the last one certainly did - leaving an exit hole twice the size of a manhole cover. The Germans at this point didn't have proximity-fused artillery shells like we did, thank God. Otherwise, I wouldn't be sitting here.

"It was a real struggle trying to navigate. Because of the damage done, the only thing we had much control over were the engines. 'Ghost' wanted to drift sideways. We managed to slow down, and that helped a bit. Once we got oriented, the goal was to set out on a homeward course in hope that we'd come across some P-51 fighter protection before the ME-109s or Focke-Wulf 190s found us. "Now hold on - there's more. The navigator in the nose called up and said another group of flak batteries was shooting at us. He could see the gun flashes. From experience, he calculated it would take about eight seconds for the rounds to reach our elevation. So we started a game of hop-scotch. The guns would fire, the navigator would shout, and we'd turn either left or right by adding power surges to one or more engines. More than one cluster of shells exploded in the air space we'd vacated just seconds before.

"The first time my crew walked into St. Dizier, we had to hold our noses. The roadside ditches were littered with German corpses. First stop was the village pub. The place was crawling with French resistance fighters, the Maquis. They looked like Mexican bandits, minus the sombreros. Most of them were packing snub-nose automatic weapons, with bandoliers of ammo draped across their chests. "One of the guys could speak some English. When I told him our bombers and fighter planes had bombed and strafed the nearby airfield a couple months earlier, he looked me straight in the eye and replied: 'I know - you killed our mayor.' At this point it occurred that I might not leave the tavern in one piece. All of a sudden he tossed his head back and laughed. Then he said: 'That's all right - he was a collaborateur allemand (German collaborator).' " scabies, and got right to work with a cure. You can't fly a plane or drop bombs or shoot down ME-109s if you're constantly scratching your posterior or whatever."The base dispensary had two big old claw-foot bathtubs. A scabies patient would step naked into the bathtub, sit down and lay back. At which point a medic began shoveling powdered cornstarch into the tub until the patient was buried up to his chin. And there he would repose, immersed for about a half-hour. I saw this with my own eyes. "When his time was up, the patient wiggled his way loose and stepped from the tub. Then another patient came forward and sat down in the second tub. The medic then began shoveling the cornstarch from the first tub into the second tub, until the patient was buried. This went on back and forth for days, until every last scabies critter was dead. I actually thought at the time they were suffocating the bugs. But on further reflection I have to think some kind of medication was mixed with the cornstarch. I never did bother to find out. "And while we're at it….the only time I saw wing commander John Jacobowitz really howling mad about something, was the morning he lined up every crew outside his headquarters and proceeded to give us a verbal flogging while we stood at attention. These were the guys that hauled all that gasoline to Patton's army for nearly a month. According to the colonel, we'd also brought something else home from the fleshpots of France. He told us fifty-six crewmen were currently being treated for clap. Incapacitating yourself for duty, he called it. Inexcusable, irresponsible behavior. As far as the colonel was concerned, the infected crew members were guilty of fraternizing with the enemy.*** "This leads me to the delicate subject of other body fluids. Every B-24 had one or more relief tubes. For every thousand feet that an airplane ascends after takeoff, the outside temperature drops about 2-1/2 degrees. In the wintertime, that meant it got around 40 or 50 degrees below zero at 22,500 feet, our bombing altitude. The first or second guy to use the tube at that height on a winter day almost always plugged it up. Frozen solid. You couldn't hot-wire the thing, or somebody might get electrocuted if it short-circuited. So the other nine crew members had no other choice than to use the bomb bay. There were four vertical bomb racks forward, two on each side of a narrow catwalk. And that's where they'd do their business. Well … the warm liquid ran down the racks and collected in the bomb bay doors below, where it instantly froze solid. It happened on a few occasions that the frozen discharge would build up and prevent the doors from opening. No matter-- the bombardier would let the bomb load go anyway. You couldn't do this in a B-17, which had reinforced barn-like doors. But the Liberator doors opened and closed like a roll-top desk, and were purposely made to break away under major stress. So the falling bombs smashed through the frozen roll-top doors and went their merry way. Whenever this happened, it really irritated the repair crews back at base. They had enough real combat damage to tend with as it was.

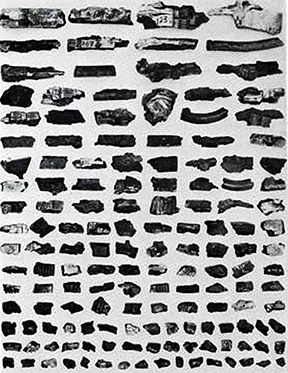

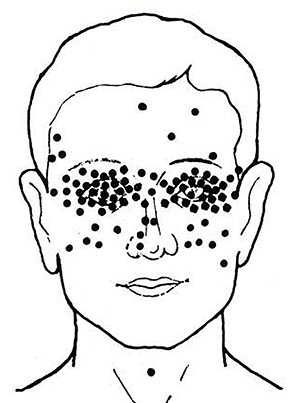

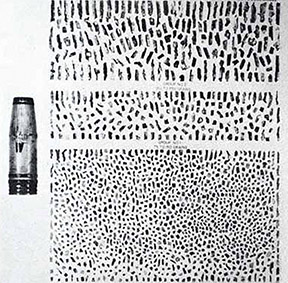

"Most every plane in the group got dinged up, some more than others. The only injury to our crew, if you can call it that, happened to the navigator, Alvin Broadway. He always wore a pair of oversized flight boots. A piece of flak came through the fuselage and sheared the sole clean off one of them, but hardly scraped the skin. One time we brought back 'Ghost II,' really peppered with flak. We got as far as 164 shrapnel holes but had to stop counting when the crew truck showed up and hauled us off for debriefing. Another time Stevie Barnes, the flight engineer, noticed a hole in the underside of the right wing. On closer inspection he found an intact 88-millimeter round lodged in the wing's interior. This made his hair stand on end. Was the shell dead as a doornail -- or a disaster waiting to happen? There was no way to tell. " Barnes got on the field telephone and called for help. A voice came on the line: 'Armament office.' Barnes explained the situation in detail, and in turn answered a number of questions. He then asked how soon a munitions expert could come by and remove the shell from hell. The voice on the other end said: 'You've got the wrong number.' And hung up. Can't say as I blame them. It took three days before we could get anybody out there to tackle the problem."

As Wendling approached the thirty-mission mark, he paid a visit to the 56th Fighter Group. His interest now focused on the single-engine P-51 fighter. But nothing came of it. Then Jack remembered two friends who flew Mosquitoes. The two-seater Mosquito - pilot and navigator/radar operator - was a British designed jack-of-all-trades fighter-bomber, made almost entirely of laminated plywood. The latest models could climb to 43,000 feet and exceed 400 mph in level flight. Twin Rolls-Royce engines, each packing 1,460 horsepower. And so Jack began a love affair with the Wooden Wonder; Timber Terror was another nickname, as evidenced by the Germans' fear of it. "The Mosquito outfit was involved in special reconnaissance - meaning more than just photo reconnaissance. Low-level snooping and intruder missions, stuff like that. I'd looked the Mosquito over and really liked what I saw. So I talked to the head honcho and he made the arrangements. I transferred in March of forty-five, after my last bombing mission. During the transition I trained in an Oxford, another British aircraft. The guy I roomed with gave me my first rides in the Mosquito. "Then the war suddenly ended. To celebrate, a couple pilots took off and flew to London, where they proceeded to buzz Buckingham Palace. The wonder was they weren't shot down. The air ministry got involved in the ruckus, and the end result was that all our Mosquitoes were transferred to some remote airfield in Scotland." ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Wendling's post-war career never strayed far from military matters. After college graduation, he was recalled to active duty in September,1949. Jack completed a five-month atomic energy course before being assigned to the propulsion lab at Wright-Patterson Field, Dayton, Ohio. Every imaginable kind of aviation engine came under the lab's scrutiny. Further assignment to the Technical Intelligence Division (a think-tank devoted to the 'prevention of technological surprises by an enemy') rounded out Jack's military career. Wendling as a civilian spent a further 21 years at Wright-Patterson, dealing with such subject as acoustics, telemetry and meteorology as they pertained to missiles, jet aircraft , space and nuclear activities. At age 31, Jack learned he was the youngest federal civil servant outside the Washington Beltway to attain the rank of GS-15. Before Wendling retired at the tender age of 48, the Force Systems Command recognized his contributions with its highest meritorious service award, the first ever awarded outside its military ranks. An Idaho resident for many years, Jack and his late wife Kathleen raised four children. "When I wasn't fishing," says Jack," I was hunting. And when I wasn't hunting, I was skiing. Don't much remember what I did in between…." "Ooh…and a bit of flying." ############# *Among

the four-engine (Heavy) bomber crews, LT Emil "Mickey" Cohen

(1924-2008) was the youngest commissioned B-17 pilot in the 8th Air

Force. Cohen flew with the 447th Bombardment Group, 709th Squadron. ***Wendling adds that Col. Jacobowitz, his 23-year-old squadron commander, graduated medical school after the war. "He once told me," Jack relates, "how amazed he was by the manner in which two hundred young guys could think up so many ways to aggravate him."

This is another in the oral history series by Tony Welch. See the other three at: SON

OF A GUN

Send Corrections, additions, and input to:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||