SON OF A An Artilleryman Follows

An Artilleryman Follows

In His Father's Footsteps

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

"I was standing on the back porch

as he drove away in his car," says Bob Lamkin. "And that's

the last I ever saw of him. I was six years old."

Lamkin, now 91,

is referring to his father, Robert L. Lamkin, a veteran of the Spanish-American

War (1898-99) and the Philippine Insurrection that closely followed.

The senior Lamkin served during the latter conflict, which claimed over

4,000 American lives. And then -- a quarter-century later -- he simply

disappeared.

What ties could

possibly link - much less bind -- a child to a father who suddenly abandons

his family?

"What I remember of my father is

that he fought as an artilleryman in the U.S. Army," Bob recalls.

"My only image of him is from an old photograph. He's in his uniform

standing beside a cannon."

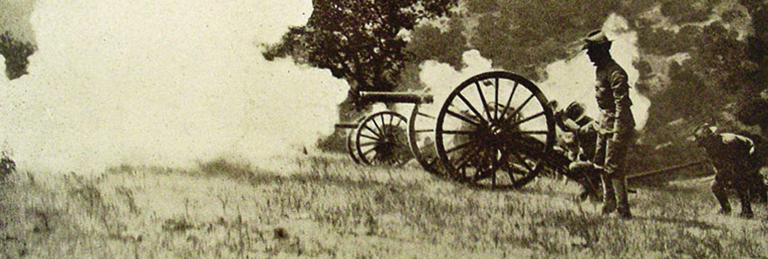

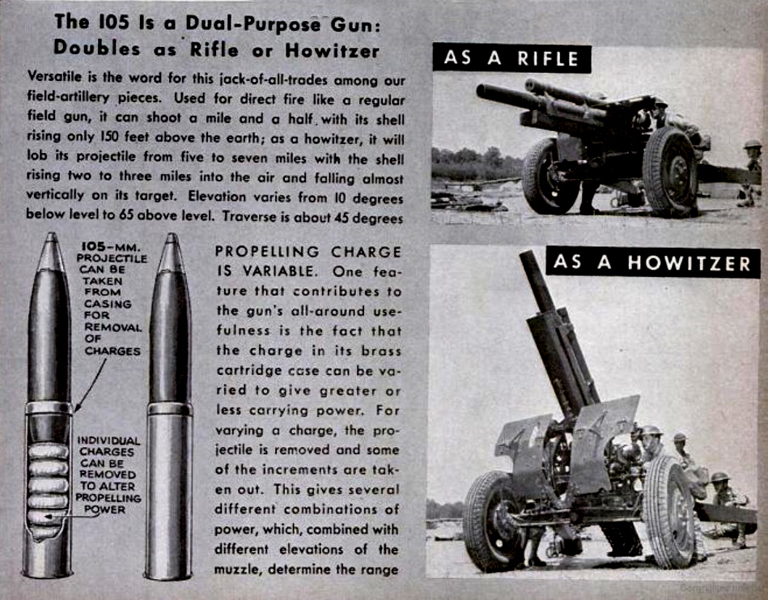

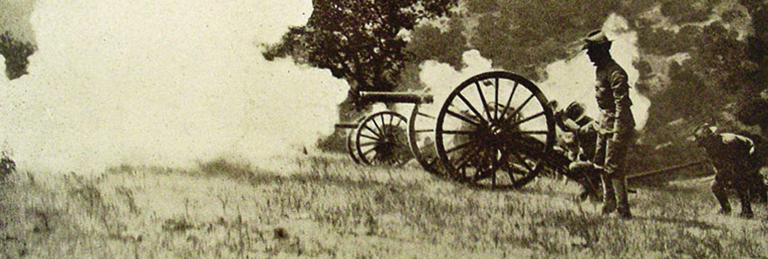

The Spanish-American War and subsequent conquest of the Philippine

islands eventually involved 126,486 U.S. troops. In this 1902

photo, a battery of 76mm Hotchkiss cannons clear the way for attacking

American infantry. Bob Lamkin's father would have helped man a

570-pound howitzer like this, pulled by a team of three mules.

|

This single connective thread, fragile though

it be, would eventually lead Lamkin to a different battlefield half a

world away. In his own time and in his own way, Lamkin managed to forge

a path that reunited him with the father he would never come to know.

But first things first. Bob Lamkin had

a few blind alleys to traverse before reaching his goal.

"I transferred to Oregon State University

as a sophomore in 1940," he explains. "ROTC was required,

and thinking back on my father I chose the field artillery (FA) rather

than the infantry or engineers." Later, Bob joined the Enlisted

Reserve Corp and remained in school until called to basic training at

Camp Roberts, California. Then off to FA officer training at Fort Sill,

Oklahoma.

|

Part way through the course, Lamkin suddenly

found himself transferred to infantry OCS at Fort Benning, Georgia.

Two weeks short of graduation, he was called before the examining

board and without explanation transferred to yet another base

in South Carolina. Surprise! Lamkin's back in artillery school.

Then as now, soldiers were apt

to use a naughty acronym - SNAFU - to describe a military mix-up.

But Bob wasn't complaining - far from it. Private Lamkin was finally

where he set out to be.

In the military, head counts are always done alphabetically. Lamkin

recalls two infantry classmates at Fort Benning by the names of

Lambert and Landis who stood either side of him at every roll

call. "They both graduated from infantry training, both were

commissioned as shave-tail lieutenants, and both died a few days

apart during the Battle of the Bulge. So you could say the board

did me a favor."

Following graduation, Lamkin's class

assembled at Boston harbor where it boarded a converted banana

boat, bound for Europe. Skipping a stopover in Britain, the ship

crossed the English channel and off-loaded on the French coast.

"We gathered up our guns and ammo and towing vehicles and

went a short ways inland to a chateau, where we hunkered

|

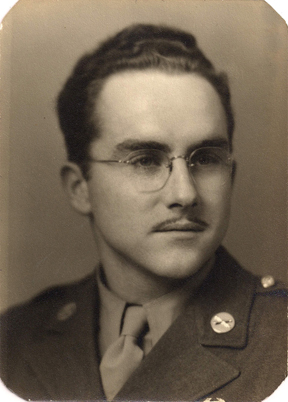

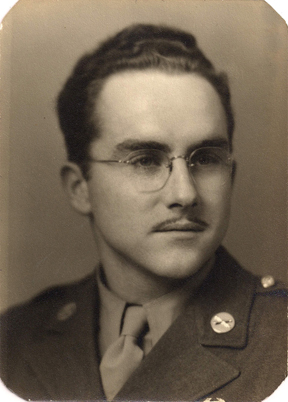

PFC Robert L. Lamkin

PFC Robert L. Lamkin

|

down. The chateau had been a Wehrmacht headquarters,

until our infantry chased them out. I think it was around the end of June,

almost a month after D-day." Bob also notes that chateau living was

a welcome surprise; Normandy had yet to fall and the battle of the hedgerows

kept dragging on. With each passing summer day, the din of battle gradually

faded as the Allies gained a solid foothold in southern France.

And then George S. Patton arrived on the scene…

Bob's battalion served under the Third Army, commanded by General Patton.

Says Lamkin: "He was always in a rush to get there first. When

Patton took off, he went like a raped ape and woe betide those who couldn't

keep up. I remember reading a story in Stars and Stripes that quoted

him as saying 'I'm going to cross the Rhine if I have to send home a

boat-load of dog tags.' That didn't sit too well with the troops, as

you might imagine."

|

These two iconic images leave little to be imagined.

A U.S. gun crew in Normandy steels itself against the sound and

fury of a fired 105mm cannon, while the sole surviving crew member

of a German 88mm ponders his fate in the aftermath of a losing

artillery duel with Russian tanks.

|

Photos

enlarge when clicked)

|

|

|

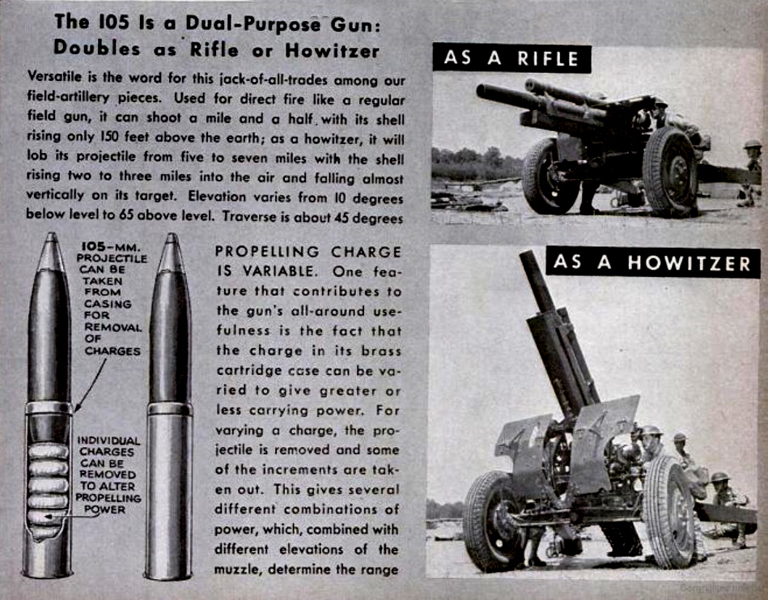

Lamkin was assigned to headquarters battery,

the command staff for the entire battalion. Each FA battalion consisted

of three batteries (A, B and C), totaling in all 12 guns and a complement

of support troops. Thus, a typical infantry division was backed up by

fifty-four 105mm howitzers, the workhorse cannon of WW11. Experienced

artillerymen in a race against the clock to engage the enemy prided themselves

in executing given commands in the shortest possible time span. Bob Lamkin

was witness to just such a performance the first time out of the bullpen

- and likely owes his very life to a set of skills perfectly planned and

promptly executed.

|

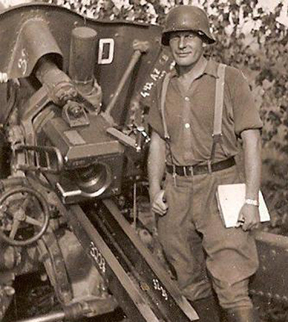

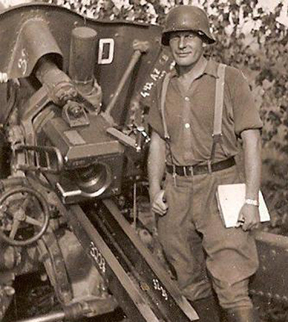

Bob Lamkin feeds the open belly of a 105-mm howitzer during the

battle of the Ardennes, while the gun captain stands ready at

the right -- paused to pull the firing lanyard the moment the

breech is closed.

|

"Our

battalion and a number of others began moving inland, until we finally

ended up in Belgium just behind the front line in an area adjacent

to where the Battle of the Bulge was going on. We had just unhooked

all twelve guns from the towing tractors.

"Without warning, a salvo

of artillery shells descended at our rear, maybe a hundred feet

away. The terrain ahead was sloped, with the hilltop facing us,

and the firing was coming from somewhere out of sight beyond the

crest," Lamkin recalls. A lethal concoction of dirt, smoke

and flying shrapnel sent Lamkin scampering for the nearest sanctuary

- a parked Jeep. Crawling beneath the framework and laying spread-eagle

to minimize exposure to what he knew was coming next, Bob clenched

his teeth and tightened his sphincter muscles. A second salvo

of equal force arrived moments later, this time exploding in front

of the battery. "Whoever was shooting at us likely had a

hidden forward observer ((FO) calling the shots," Lamkin

explains. Bob tried further to shrink himself in anticipation

of the grand finale --- the gunners were about to split the difference

and drop the last load right on target.

Just as suddenly, Lamkin relates,

the air overhead was rustled by the

|

|

passage of numerous artillery shells coming from various directions.

Ever alert, the headquarters command post had simultaneously contacted

no less than thirty-one other batteries scattered around a five-mile

area, and provided them with estimated co-ordinates of the enemy's

location. A blanket of destruction - well over 100 shells - saturated

the distant landscape in what is termed a TOT (time on target)

concentration. "Very lucky for us," Bob grins. "We

never did get that third salvo."

As a matter of record, artillery 'serenades'

on the battlefields of Europe occasionally reached eye-popping

proportions. In a single nighttime engagement, an attacking battalion

of German infantry was stopped in its tracks by a defensive barrage

totaling 11,500 rounds in various calibers, including 155mm. During

the Battle of the Bulge, U.S. artillery fired an estimated 1,225,000

rounds from 4,155 "tubes," as cannon barrels were labeled

by their handlers. To be sure, the infantry paid all due respect

to incoming rifle and machine gun fire. Beyond that, artillery

(and its first cousin, the mortar) were horses of another color.

Incoming artillery barrages that seemed to go on forever - thirty

minutes of continuous drum fire was not uncommon -- often left

survivors on both the Allied and Axis sides "cringing, crapping

and crying" in their foxholes - as one GI lyrically put it.

Between August 1 and November 30, 1944, Third Army medics catalogued

the following physical damage; for every gunshot

|

A gunner of the 4th

SS Polizei Panzer Division

tends to his firing chart: azimuths, base lines, traverse circles,

grid coordinates and a host of other calculations all affect the

degree of accuracy.

A gunner of the 4th

SS Polizei Panzer Division

tends to his firing chart: azimuths, base lines, traverse circles,

grid coordinates and a host of other calculations all affect the

degree of accuracy. |

wound, there were two explosive shrapnel

wounds. No such tally was kept of the dead.

An advancing Sherman tank

falls prey to a poorly concealed 75mm PAK 40 manned by

a German crew. The

PAK 40 was capable

of penetrating 4.5 inches of armor at 500 yards.

An advancing Sherman tank

falls prey to a poorly concealed 75mm PAK 40 manned by

a German crew. The

PAK 40 was capable

of penetrating 4.5 inches of armor at 500 yards. |

Once business in the Ardennes

was attended to, the battalion was re-assigned in support of a tank

corps. Exiting Belgium into Germany in late January, 1945, Lamkin's

battery spent day after day in relentless pursuit of the retreating

Germans - further evidence of General Patton's desire to lead the

pack.* "We'd move into an area and get set up. Then the tanks

would pass through until they met enemy strong points. If that didn't

get the job done, they'd back off and we'd take a crack at it. Then

the infantry moved in." ** Not once did Lamkin's group ever

have to resort to direct fire. "That's when you shoot directly

at a visible target on the ground," he explains. "All

our distant firing at unseen targets involved a lot of computation

and co-ordination. We used high explosive (HE) shells almost exclusively.

Some exploded on contact, some we set for air-burst." Though

assigned to duties within the headquarters command staff, Lamkin

got in his fair share of licks behind the Model M2A1 |

howitzer as a breech loader

- or ammo man. What he couldn't keep track of were the number of times

his battalion picked up and moved. Like playing a continuous game

of hop-scotch and leap-frog, as Bob puts it.

Once over the Rhine River

via a pontoon bridge, the battalion skirted Cologne and continued

cross-country into Bavaria, with stops at Schweinfurt and Frankfurt.

"We only paused if a target was assigned to us," Lamkin

notes. Unlike the front line infantry, who were obliged to dig new

foxholes most every time they moved, cannoneers enjoyed the 'luxury'

of sleeping bags spread out on the ground covered by shelter halves

- so called because two men, each joining together a canvas half shelter

-- were provided a measure of protection from the elements.

|

Lamkin's battalion wasn't exactly

on a guided European tour, though on rare occasions it seemed

that way. Next stop: Czechoslovakia - country number five. Lamkin

soon discovered there were other 'tourists' out and about, enjoying

the springtime blossoms and other amenities. "We were heading

for Vienna, Austria, when the news came down that Germany had

surrendered," Bob relates. "A few days later several

of us were checking out a small village when we came across a

farm house with some activity going on. What do we find but a

half-dozen Soviet soldiers. So we all sat around celebrating and

got kinda drunk on Russian vodka."

Fortunately, none of the men in Bob's

battery were killed, nor did they suffer any battle wounds by

war's end. Returning to Germany as part of the occupation forces,

Lamkin and half-a-dozen buddies were assigned to the 115th FA

Battalion motor pool in Frankfurt. "It was a great time for

us," he reveals. With virtually the entire German transportation

system smashed to smithereens, getting around proved a major challenge.

"In the beginning," Bob notes, "the only thing

we had to worry about was the

|

Strict rationing of a dwindling

supply of ammo from October 11 - November 7, 1944, restricted

the Third Army to twenty 105mm rounds per-gun-per-day -- in all,

76,000 shells. The subsequent drawn-out Battle of the Bulge far

exceeded that sum on any given day.

Strict rationing of a dwindling

supply of ammo from October 11 - November 7, 1944, restricted

the Third Army to twenty 105mm rounds per-gun-per-day -- in all,

76,000 shells. The subsequent drawn-out Battle of the Bulge far

exceeded that sum on any given day. |

upcoming invasion of Japan. At one point

we actually trained for that, until the Japanese surrendered in August."

The motor pool assignment, says Lamkin, proved to be a gold mine in disguise.

Senior officers and master sergeants - the ones who ruled the roost and

had the power to return favors - made heavy use of the vehicles under

Lamkin's care. The twinkle in Bob's eye suggests that a barter service

second to none flourished within the battalion.

This Krupp-made K5 Tiefzug

(one of 25 manufactured) was the most successful long-range railway

gun of WW11, capable of delivering a quarter-ton shell 40 miles.

The gun's 105-foot barrel lining was rifled with twelve quarter-inch

grooves, resulting in the petal-like smoke pattern seen here.

Note all the fingers in the ears.

This Krupp-made K5 Tiefzug

(one of 25 manufactured) was the most successful long-range railway

gun of WW11, capable of delivering a quarter-ton shell 40 miles.

The gun's 105-foot barrel lining was rifled with twelve quarter-inch

grooves, resulting in the petal-like smoke pattern seen here.

Note all the fingers in the ears. |

And then

there was the irony of it all. Wars are loaded with the ironic;

scattered events have a propensity for linking up with one another.

One chance happening leads to another and - voila! To wit:

"From time to time,"

says Lamkin, "some of us were called on to help man the checkpoints

along a major roadway. We were on the lookout for certain documents

issued to returning German veterans by the occupational authorities.

If they possessed such signed and stamped documents, we let them

pass. It was their ticket back to civilian life. Those others

men who lacked such documentation were turned over to the MPs

and sent to a POW camp for further interrogation and disposition.

"One day this young man approached

the checkpoint. He looked to be in his early twenties - around

my age. He spoke perfect English, no accent. His papers -- everything

was in order. I noticed his clothes were a mix --- half military

and half civilian. We got to talking and swapping stories about

where we'd been during the war, and what our duties were. As he

got deeper into the details, it slowly became evident that this

fellow standing just a few feet away had once tried his damndest

to kill me."

A further exchange of background revealed

that the detainee's parents had immigrated to America just after

WW1 and settled in the Midwest - Iowa, to be exact. Their son

had paid relatives in Germany an extended visit just before the

war broke out - which timing proved disastrous. Despite his status

as an American citizen, he'd been drafted and assigned to an armored

regiment. In his fourth year of combat and now an

officer, he found himself fighting on the western front.

|

"He turned out to be a commander in

a Panzer brigade," Bob explains, "and it was his battle group

of Tiger and Panther tanks that attacked us with their seventy-six and

eighty-eight millimeter cannons that day in Belgium. He told me our plunging

artillery fire had destroyed or crippled nearly half his armored force."

A second chance encounter proved even more

dramatic, containing as it did all the elements of a Shakespearian tragedy.

"Not too far away there was a liberated

concentration camp," Lamkin continues, "and it was fairly common

to come across former inmates wandering around. One day this figure came

down the road, and when he saw us he turned and cut across a field. We

fired a few machine gun rounds in his direction and that got his attention.

So here's this Jewish kid, 14 years old. He told us he'd escaped twice

from the camp during the war, each time from a lineup leading to the gas

chambers. How he managed that, I can't imagine. We let him hang around

and he'd scrounge food from nearby farms."

| "One

day we were checking out this fellow whose papers appeared in order.

All decked out in civilian clothes. The kid happened to wander up

and when he saw this guy, he took off running. One of the guards

chased after the kid and brought him back. He pointed at the man

and said he was a SS major (sturmbannfuhrer) in the concentration

camp. We ordered the man to take off his shirt and there -- sure

enough -- was a SS tattoo*** under his arm.

"We decided it was the kid's

turn at bat. Somebody got a shovel, and on the sly I removed the

ammo from my carbine. We shoved the German over on the shoulder

of the road and told him to start digging. I gave my rifle to

the kid and told him he was in charge."

"So here's this SS officer

digging away. Every time he paused to catch his breath, the kid

would jab him in the arse with the rifle barrel and shout 'schnell

- schnell !' The grave was maybe two feet deep when suddenly

the guy fell to his knees, and with folded hands begged the kid

for mercy. We ordered him out of the hole and turned him over

to the MPs. Not long after we heard a solitary shot in the distance.

"And, you know… I still

wonder about that to this day"

|

A grinning John Kelly (luck

of the Irish?) examines his helmet, battered but not penetrated

by a nearly-spent chunk of flying shrapnel. Even well dug-in infantrymen

most dreaded being caught in a heavily wooded forest; incoming

artillery rounds exploded on contact with the tree tops, driving

shrapnel into their fox holes and shelters.

A grinning John Kelly (luck

of the Irish?) examines his helmet, battered but not penetrated

by a nearly-spent chunk of flying shrapnel. Even well dug-in infantrymen

most dreaded being caught in a heavily wooded forest; incoming

artillery rounds exploded on contact with the tree tops, driving

shrapnel into their fox holes and shelters. |

##############

| |

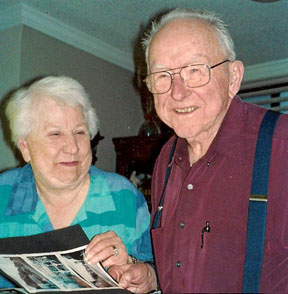

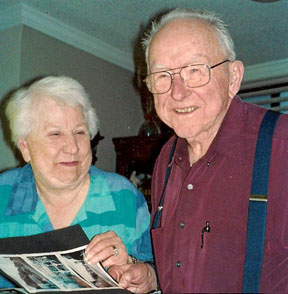

Lamkin and his wife of 62

years, Alma, reside in a suburb of Portland, Oregon. After finishing

college, Bob spent the majority of his working years in industrial

sales. "Most of my closest friends have passed on,"

he says. "A couple times we talked about having a reunion

in Switzerland, but somehow it never happened."

Lamkin and his wife of 62

years, Alma, reside in a suburb of Portland, Oregon. After finishing

college, Bob spent the majority of his working years in industrial

sales. "Most of my closest friends have passed on,"

he says. "A couple times we talked about having a reunion

in Switzerland, but somehow it never happened." |

|

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* The Third Army under Patton fought

continuously for 281 days. No other army in military history ever advanced

farther and faster. Third Army killed, wounded and captured some 1,811,388

enemy combatants - six times its own strength in manpower.

** "I am the Infantry. Queen of Battle."

"I am the Artillery. King of Battle."

The King puts it where the Queen wants it.

(wall placard in the field artillery Enlisted Men's Club, Fort Sill,

OK., 1947)

*** The SS tattoo (Blutgruppentatowierung)

was worn by members of the Totenkopfverbande--SS to identify

an individual's blood type - A, B, AB or O. Application was on the underside

of the left upper arm. It served to identify blood type in case a soldier

was unconscious and in need of a transfusion.

This is another in the oral history series

by Tony Welch. See the other two at:

GATE

CRASHER VS. POTATO MASHER

THE REAL

WORLD RECORD MUSKY

About

the author

Send Corrections, additions,

and input to:

WebMaster/Editor

Click

the star for

Site Map  .. ..

|

|