|

Click any image for a larger view

GATE CRASHER

VS.

POTATO MASHER

A Screaming Eagle Goes Airborne on

D-Day – Twice

The Leonard Hornbeck Story

By Tony Welch

Barely recognizable in the false dawn of

D-Day, a German grenade skitters across the roadway. Walking directly

into its oncoming path is an American paratrooper.

At age 23, Leonard Hornbeck's reflexes have never been sharper. Instinctively,

he jumps straight up just as the “potato masher” disappears

beneath his combat boots. In that frozen moment of time the grenade explodes

between Leonard's legs, propelling him skyward. If the German soldat

who tossed the grenade tried to duplicate his feat - performed in the

dark - he would have gone through a case of explosives without coming

close.

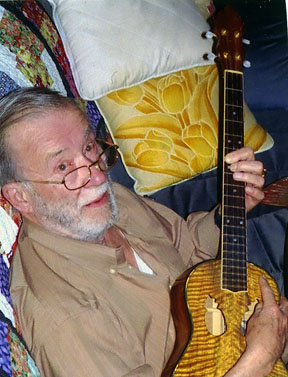

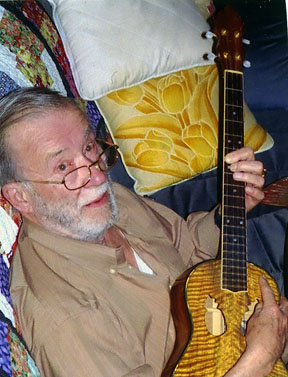

Hornbeck's

sitting across from me now, sporting his customary smile. In a few

weeks he'll turn 90. His wife Katherine has planned a party, with

relatives traveling to Oregon from as far away as Texas. Among the

participants will be Len's two daughters, Paula and Paulette, as

well as a scattering of grand-children.

Of the 15,600 potential story tellers who descended by parachute

from the darkened skies on June 6, only a fraction will leave a

written record of their hazardous undertaking. Hornbeck's voice

numbers among the dwindling Currahees*

yet to be heard.

My chance encounter with Tech Sergeant Leonard I. Hornbeck occurred

in a doctor's office. His airborne cap was cluttered with a dozen

ceramic pins and decals. I inquired: "The hundred and first?"

Big grin. Then: "The five-oh-sixth?" His grin widened.

Standing off to the side, Leonard's wife eyed me suspiciously; maybe

I was peddling burial plots - or worse, variable annuities.

|

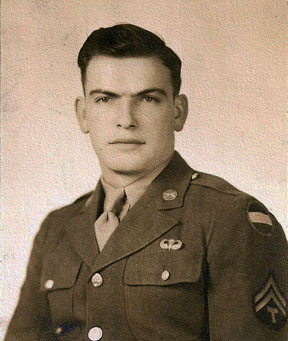

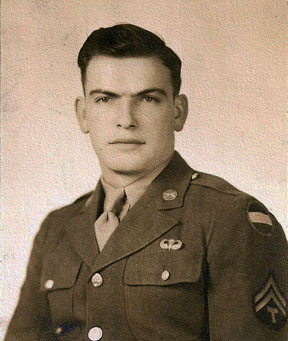

Leonard Hornbeck

Leonard Hornbeck |

Hornbeck cautioned me up front about

his failing memory. In turn, I confessed to having misplaced a dozen car

keys of my own - plus the cars. "Let's you and me try putting the

pieces back together," I suggested. Another mile-wide smile.

I noticed Leonard

was stocky, with a fulsome chest and stout shoulders. No paunch. And

biceps, I imagined, that still rippled beneath his long shirt sleeves.

It's his legs that aren't up to snuff. In recent years Leonard's come

to depend on a walker for mobility. "The pain's never entirely

gone away from day one," he confides. Meaning D-day, 66 years ago.

Beginning in his mid-teens, Leonard spent

the greater part of his working life as a logger in northwest Washington

State. At five feet four inches, Hornbeck barely exceeds the height of

the old growth stumps he left in his wake. Upon reaching his mid-seventies,

Leonard finally quit the woods and sold his sawmill. His grandsons recall

teaming up with him as teenagers during summer vacations. Says Jeff Coles:

"That's when I made up my mind to go to college. I'd look around

- ooof! All those trees far as I could see."

One of seven children,

Hornbeck moved north with his family from Roseburg, Oregon to the village

of Concrete, Washington in the late thirties. His father worked for

the Bureau of Public Roads, a federal agency. Like many of his youthful

contemporaries, Leonard was attracted to the mystique of aviation; it

was 1941, fascism was aflame in Europe, and the U.S. Armed forces were

actively recruiting - in certain categories, very selectively.

|

"Hey, ma --

it's me!" In this fading photo,

mailed home, Hornbeck waves a greeting

to his mother Carrie Jane as he prepares to

board a C-47 for the third of five required

training jumps at Fort Benning, Georgia.

| "I wanted

in the worst way to be an aviation cadet - that was the biggest

challenge I could think of," Leonard explains. "So I enrolled

in Mount Vernon Junior College to make up for my shortage in math

courses, and that helped me pass the written test. What I didn't

figure on was failing the physical." Though he made a number

of determined inquiries, Hornbeck was never told the reason. "I

strongly suspect they had too many applicants who qualified, and

this was their way of letting the surplus down gently - rather than

just saying we can't use you."

Hornbeck then shifted his attention to communications technology,

and on completing the college program applied for active duty in

the army. Following basic training

at Camp Roberts in California, Leonard was assigned to a communications

course. But his lust for the wild blue yonder went right on raging.

|

Enter the paratroopers,

center stage. "They were certainly up in the air," Hornbeck

reasoned, "and that's exactly where I wanted to be." Accepted

in l942, Hornbeck began training in the fall at Fort Benning. He completed

many forced marches and the mandatory five parajumps required of every

applicant, followed by advanced communication schooling. During this

period, the recently formed Five-O-Six regiment showed up at Benning.

"We had a nickname for those guys -- the Walkie-Talkie Non-Jumpie

outfit," Leonard reveals. "And now here they were. A lot of

them were draftees. I was willing to be assigned most anywhere, but

not there. So guess what? - suddenly I'm a Five-Oh-Sixer."

Airborne uniform patches are

varied and inventive. Among the many identifying

adornments are, from left: the 506th PIR patch (lucky eleven), the

Band of

Brothers (HBO TV series on Company E), and the 101st Airborne patch

- original

issue, 1944. Patches worn in WW11 combat zones fetch high prices among

collectors.

Now

an instructor, Hornbeck found himself thrust into the midst of the

newly arrived parachutist wannabes. His concerns soon dissipated.

"It took about two or three weeks before I discovered that my

earlier impressions were completely unfounded. I began to make a few

friends. One of them was Bob Plants. Much later on, Bob and I were

among a group that took a test to determine who would fill a couple

advancement slots. Bob came out on top and at age 21 became a master

sergeant. I scored right behind him and went from corporal to technical

sergeant."

The subsequent ocean voyage to England in September 1943 passed without

incident, and was soon followed by more intensive training. The 82nd

and Hundred-and-First were competitive, both in the air and on the

ground. Sometimes it got downright personal, leading to a flash point

that begged for a resolution.

Says

Leonard: "This one guy, he made a remark or two about my height.

He was the arm wrestling champ of the Eighty-Second. So I sat him

down and we planted our elbows on a table." But it didn't end

there, Hornbeck adds. When word got out, the reigning champ of the

101st showed up with fire in his eye and a cocked elbow. Leonard pinned

him too, for good measure.

| Hornbeck spent two weeks

with a British paratroop battalion, whose members had been bloodied

but unbeaten in North Africa. They would likely meet Americans again

on French soil, and the Brits thought it important to become acquainted

with their allies in advance. "During the visit, they set me

up in a swimming class," Leonard remembers. "Well...I

sank like a rock."

A worse scare

for Leonard occurred during a nighttime exercise, one that came

dangerously close to undermining the 506's determined effort to

reach a certain skill level in preparation for D-day - date unknown.

"Poor planning, that's what it was," Hornbeck avows.

"Can't blame what happened on high winds or bad weather -

there was neither that night." Whatever the

|

Having defeated the reigning

arm wrestling champs of the 101st and 82nd airborne divisions

65 years ago, Len Hornbeck goes elbow to elbow with grandson Rodney

Coles (210 pounds). Note the distressed look on Rod's face and

the distorted blood vessels on his forearm.

Having defeated the reigning

arm wrestling champs of the 101st and 82nd airborne divisions

65 years ago, Len Hornbeck goes elbow to elbow with grandson Rodney

Coles (210 pounds). Note the distressed look on Rod's face and

the distorted blood vessels on his forearm. |

snafu, the sticks exited over terrain that

was sharply sloped. Many of the troopers slammed into the banked hillside,

resulting in numerous injuries - some serious. Leonard himself blacked

out. "My lower torso and back took a beating," Hornbeck reveals,

"and all this happened about two weeks before D-day. I was still

in considerable pain and discomfort, but I never let on once I left the

hospital. I'm sure a whole bunch of other guys kept quiet, as well."

June 5, 1944. 506th regimental

headquarters personnel prepare to board a C-47, one of three Skytrains

carrying command, demolition and communication specialists to

Normandy - Hornbeck among them.

June 5, 1944. 506th regimental

headquarters personnel prepare to board a C-47, one of three Skytrains

carrying command, demolition and communication specialists to

Normandy - Hornbeck among them. |

The night drop onto the Cotentin Peninsula

was an extremely complex undertaking, with the initial thrust provided

by 15,600 paratroops of the 101st/82nd loaded aboard 821

C-47 Skytrains.

Leonard's triple-plane element

carried headquarters personnel from all three regiments, mainly

communications specialists - of whom only a handful were able to

locate their regiments late on D-day Their first adversary was a

fog bank overlaid with broken clouds, encountered just inland. The

ensuing confusion resulted in numerous navigational errors. Then

suddenly the sky cleared, and almost immediately the night lit up

with tracers. Gunner Helmut Grahns, 19, |

rousted from bed, recalls tracking the aerial

convoy with his quad-barreled flak gun. "I was wearing only my helmet,

boots and a long night shirt - what a sight." After the armada had

passed, Grahns counted 373 empty 20mm shell casings scattered around his

Swiss-made anti-aircraft weapon - plus a pair of crashed C-47s burning

a mile away.

Hornbeck's element,

unscathed, overshot its drop zone by more than a dozen miles. Time:

around 01:30 hours. Estimated altitude: 500-600 feet. Leonard kicked

out a pile of equipment bundles, including a SCR 300 radio, then stepped

into space. "I don't know how unusual it was, but we had no officer

aboard," Leonard notes. "Bob Plants held the senior rank,

and the two of us were in charge. Bob brought up the rear as jump master."

Any pent-up uneasiness

about falling through the night sky was instantly replaced by a dread

of the unknown - the unseen fate that awaited Hornbeck and his companions

once on the ground. Leonard hit the deck feet first, tumbled in a ball

and quickly regained his feet. "All my aches and pains from the

night jump in England - they just disappeared. All I felt at the moment

was acute anxiety."

|

Hornbeck

clutched his cricket and started walking. Within 45 minutes everyone

in the 18-man stick was accounted for. The group took a compass

bearing and set out in the general direction of Utah beach. Plants

took the point and Hornbeck the rear. Their objective: to help

block any German reinforcements from reaching the landing beaches,

and to assist the 4th Infantry division in pushing inland along

the southern causeways. The countryside was spotted with occasional

flooded fields, mostly ankle deep, bordered by tree-lined hedgerows.

Shortly they came upon other scattered parachutists. Among them,

a supply officer. The lieutenant wanted to assume command, but

after a heated discussion it was decided he best just tag along.

"This didn't sit too well, but he was outnumbered,"

Leonard chuckles.

The group,

now strengthened to about 50 men, chanced upon a country road

heading toward the coast. Leonard reckons they'd advanced 500

yards or so, when the grenade from nowhere bounced between his

feet. Hornbeck might well lay claim to being the only member of

the Hundred-and-First to go airborne twice on D-day and live to

tell about it. "The guy closest to me swore I shot straight

up in the air for a good fifteen feet. But you know

|

Adversarial counterparts

to the 101st Airborne were the Fallschirmjagers, Germany's

battle-hardened paratroop formations. In a surprise attack,

the 6th Parachute Regiment sent a reduced platoon of some 50

men against an advancing regiment of the 90th U.S. Infantry

Division on the outskirts of Carentan. Caught in an outflanking

maneuver and deadly crossfire, the 90th suffered many casualties

and surrendered 265 men, including 11 officers. Oberfeldwebel

Alex Uhlig hatless), seen here giving last-minute instructions,

led the assault for which he was later awarded the Knight's

Cross for valor. Uhlig was himself made prisoner three days

later and thus survived the war. He passed peaceably abed in

2008, age 89.

|

paratroopers - they exaggerate a lot."

In shock, Hornbeck

lay on his back for a few minutes, struggling to regain his breath,

then forced himself to his feet. To his surprise -- and relief--- he

found he could still shuffle along despite the throbbing pain in his

legs and groin. The column resumed its march, intent on avoiding further

contact with the enemy in order to reach their assigned area. But that

wasn't to be. Within two miles they encountered a sizable force of grenadiers

well armed and organized, blocking their way. "They really opened

up on us," Leonard recalls. "We went to ground and returned

their fire, but it quickly became evident we couldn't match their firepower.

When our ammo began running out, they jumped up and outflanked us. We

held a pow-wow and decided it was all over."

Leonard

Hornbeck shows wife Katherine his escape route from Stalag 111B.

A thousand of Hornbeck's fellow POWs were marched out of the camp

in late February, 1945 to avoid the advancing Russians —

with deadly consequences.

Leonard

Hornbeck shows wife Katherine his escape route from Stalag 111B.

A thousand of Hornbeck's fellow POWs were marched out of the camp

in late February, 1945 to avoid the advancing Russians —

with deadly consequences. |

The bitter

pill that Hornbeck chose to swallow still sticks in his craw.

"The grenade was a big disappointment to my ego, I'll say

that," Leonard explains. "But surrendering...."

His voice trails off. "When you set out on an undertaking

the likes of D-day, the only thing that matters is how you handle

the responsibility you've worked so hard to be entrusted with.

So in that regard, I feel that I failed."

The last time

Hornbeck saw master sergeant Robert Plants, the latter was speaking

earnestly with a German officer. "I'm pretty certain that's

how I got off the battlefield," Leonard notes. "Bob

somehow persuaded them I needed immediate medical

|

attention,and it wasn't long before they

put me in a truck and off I went." By late afternoon Leonard found

himself in the city of Valognes, 12 miles southeast of Cherbourg. Hospitalized,

Hornbeck underwent a physical. A German surgeon scrutinized Leonard's

pelvic area, then declared: "Ihre Mannlichkeit ist intakt."

Translation: "Your maleness is intact." Followed by a toothy

Hornbeck grin, it might be imagined - plus a sigh of relief.

"The doctors never found so much

as a speck of shrapnel anywhere," Hornbeck explains. "The

explosive shock wave did all the nerve and muscle damage." Had

the potato masher been a fragmentation grenade, rather than a concussion

device, Leonard would almost certainly have made the list of 231 Currahees

from the 506th regiment who died in the battle for Normandy.

Leonard remained

hospitalized for three weeks. On June 24, the Allies carpet-bombed Valognes

into utter ruin. Roughly half the hospital was destroyed; Hornbeck's

ward only narrowly escaped. The surviving POW patients were transported

inland, eventually passing through Paris after numerous interrogation

stops and in-transit delays.

|

"Once we

crossed the border into Germany, it seemed nobody wanted us,"

Leonard continues. "We were either standing around under

guard in open fields or else shunted by train between towns."

At one stop - a city heavily bombed by the British the night before

- Leonard and his fellow POWs were hustled out of their boxcars

and made to stand in a group on the station platform. Understandably,

the mood of nearby civilians became increasingly ugly.

"This

German in the crowd came forward, a guy around fifty years old,"

Hornbeck continues. "He commenced cuffing my ears, but good.

And he wouldn't stop. Finally a couple guards walked over and

dragged him away. I'm guessing maybe his family had been killed

or injured in the bombing." Such railway station encounters

occurred many hundreds of times during the war, occasionally with

fatal consequences.

Leonard eventually

ended up in Stalag 111B, a sprawling enclosure located 60 miles

SE of Berlin. The camp held a mixed bag of Russians, French, Serbs,

Croatians and rebellious Hungarians - some 50,000 captives in

all, of whom 5,000 were American and 30,000 were Soviets. Hornbeck's

scanty recollection of 111B events appears to be influenced as

much by the lethargic atmosphere typically associated with imprisonment

as by the dimming passage of time itself. To wit: Do you remember

ever going to a movie? Movies...no. Do you recall seeing any

|

During the 10-week Normandy

campaign, Allied losses very nearly equaled those of the Germans

--- 220,000 killed/wounded/missing, vs. 230,000 Axis casualties.

Here, camo-clad Waffen-SS panzergrenadiers carefully scope

the Normandy landscape for signs of renewed enemy activity. The

21st Panzer was the first division thrown into action on D-day;

it later defended the hub city of Caen for many weeks and was

only driven out by multiple saturation aerial bombardments, leaving

During the 10-week Normandy

campaign, Allied losses very nearly equaled those of the Germans

--- 220,000 killed/wounded/missing, vs. 230,000 Axis casualties.

Here, camo-clad Waffen-SS panzergrenadiers carefully scope

the Normandy landscape for signs of renewed enemy activity. The

21st Panzer was the first division thrown into action on D-day;

it later defended the hub city of Caen for many weeks and was

only driven out by multiple saturation aerial bombardments, leaving

35,000 French inhabitants homeless. |

theatrical plays staged by your fellow inmates?

No. What about any live musical performances? No. Did you ever visit the

camp library? What camp library...? Were there any escape attempts while

you were there? No. Was there a secret radio receiver in camp? Not that

I ever heard of. Consciously or unconsciously, Hornbeck has blotted these

various activities from his memory. Baseball, for example, proved a huge

morale builder at 111B, with uniforms that exactly duplicated major league

teams in the States. Hornbeck recalls none of it.

The only three items

that remain vivid in Leonard's memory: the arrival of Red Cross packages

(and their importance), battalions of anti-American bedbugs, and his

encounters with what appears to be a remarkable number of German military

personnel who once resided in the United States. " I must have

talked to close to fifty Germans while being moved around Germany who

claimed to have lived in America. Some of them spoke better English

than I did." On reflection, it's likely that the German POW prison

system actively recruited bilingual personnel as a means to enhance

communications between captured and captors - including evesdropping

on the always-scheming kriegies.

|

a

Sergeant Angelo Spinelli,

signal corps combat photographer made prisoner in North Africa,

put his POW time in Stalag 111B to good use. A non-smoker, Spinelli

bartered Red Cross cigarettes with a camp guard, receiving in

return this Voigtlander 35mm camera and film with which he secretly

took some 1,200 photos of camp activities. Although he cannot

recollect meeting Spinelli, who post-war published an illustrated

book of camp life, Hornbeck may well appear in one or more of

the book's many photographs. a

Sergeant Angelo Spinelli,

signal corps combat photographer made prisoner in North Africa,

put his POW time in Stalag 111B to good use. A non-smoker, Spinelli

bartered Red Cross cigarettes with a camp guard, receiving in

return this Voigtlander 35mm camera and film with which he secretly

took some 1,200 photos of camp activities. Although he cannot

recollect meeting Spinelli, who post-war published an illustrated

book of camp life, Hornbeck may well appear in one or more of

the book's many photographs.

|

"The Russians are coming!

The Russians are coming!" Beginning in January, 1945, the Stalag

111B administration began assembling groups of prisoners for transit.

Leonard finally made the list in late February, moving out in a

thousand-man group. It's departure had been dangerously delayed,

for which a tragic due bill was shortly forthcoming.

Less than an hour into their journey and just east of the Oder River,

the POWs walked headlong into a trio of parked T-34 tanks. The Russian

tank gunners briefly hesitated, then opened up with automatic weapons

fire. The leading element bore the full brunt, with nearly a dozen

men falling dead or wounded. As word spread to the middle and rear

of the column, the POWs abandoned the road and scattered. The guards

simply vanished. With calm restored - the Russians having realized

their mistake - a survey was taken and most of the prisoners elected

to return to 111B. But Hornbeck and half-a-dozen fellow inmates

decided to keep going.

Their journey was a long and perilous

one - rather |

resembling a foot-sore, ragtag excursion

with no immediate destination. The intent was to connect with either American

or British forces, but none were to be found. Finally acknowledging

their dilemma, Leonard

and his group crossed into

Poland and headed for Warsaw. Food and shelter enroute proved scarce;

conversely, nasty surprises were plentiful at nearly every turn.

Entering an abandoned house, Leonard pulled back the covers on a

down-filled bed in eager anticipation of a blessed night's sleep.

But Hornbeck had company; a youthful female stared back, sightless.

Either a suicide, Leonard reflects, or more likely the victim of

yet another drunken Russian soldier. The Dirty-Half-Dozen, as they

might be labeled, also learned not to hitch rides in open trucks,

having once been frost-bitten by the onrushing night air. Through

it all, Leonard nurtured a soft spot for the Polish civilians who

so willingly shared what little they had. "Once we were invited

to join some Russian soldiers roasting a pig over an open fire,"

Hornbeck recalls. "We filled our bellies but there was still

a good bit left over. So I asked the Russians if I could give the

rest to some Poles." A torrent of Russian curse words filled

the air, and Hornbeck quickly abandoned the idea.

Continuing their trek, the group reached

the Ukrainian border. Leonard was still wearing his tattered D-day

jump suit. Attempting to cross,

the POWs were stopped and forbidden entry. But rather than simply

sending them on their way, this time the Russians placed them in

detention. |

At its peak (1942), there

were 120 POW camps in Germany and occupied Poland holding captives

representing ten nationalities. Mortality rate among Russian prisoners

- facing near-total neglect and often confined in open-air compounds

- peaked at 6,000 per day by January, 1942, with dozens of documented

cases of cannibalism. Of the 5.6 million Soviet captives, only

1.5 million survived to war's end. In this scene, desperate Russian

POWs attempt to beg or barter for food scraps over a barbed wire

enclosure. German guards often shot at prisoners of other nationalities

for tossing food or medicines into the Russenlager enclosures.

Stalag 111B, Hornbeck's "home" for eight months, alone

held 30,000 Soviets.

At its peak (1942), there

were 120 POW camps in Germany and occupied Poland holding captives

representing ten nationalities. Mortality rate among Russian prisoners

- facing near-total neglect and often confined in open-air compounds

- peaked at 6,000 per day by January, 1942, with dozens of documented

cases of cannibalism. Of the 5.6 million Soviet captives, only

1.5 million survived to war's end. In this scene, desperate Russian

POWs attempt to beg or barter for food scraps over a barbed wire

enclosure. German guards often shot at prisoners of other nationalities

for tossing food or medicines into the Russenlager enclosures.

Stalag 111B, Hornbeck's "home" for eight months, alone

held 30,000 Soviets. |

Hornbeck well remembers

helping dig a latrine trench much like this one at Stalag 111B.

"Got a lot of exercise," Leonard recalls. Dysentery

in camp was rampant - far more prevalent than the common cold.

Wide wooden planks laid across the open ditches served as commodes;

toilet paper consisted of - whatever. Motto: "Rain, snow,

shine - watch your step!"

Hornbeck well remembers

helping dig a latrine trench much like this one at Stalag 111B.

"Got a lot of exercise," Leonard recalls. Dysentery

in camp was rampant - far more prevalent than the common cold.

Wide wooden planks laid across the open ditches served as commodes;

toilet paper consisted of - whatever. Motto: "Rain, snow,

shine - watch your step!"

|

Weeks passed, and then without

warning the group was put on a train headed for the port of Odessa

on the Black Sea. On the same train was Bill Pledger, a Buffs

regiment British rifleman taken prisoner in 1940 - who spent 3-1/2

miserable years laboring in a Silesian coal mine before escaping.

For Pledger,

arrival at Odessa proved to be his 'day of days.' "I remember

about a thousand men gathered together - French and American G.I.s

mostly, plus some paratroopers from the 101st. It was quite a

stirring march to the quay, led by a Russian Army band. We passed

by the Potemkin Steps, made famous in the silent film about the

Russian Revolution."

At dockside,

Pledger and Hornbeck and all the others boarded the S.S. Highland

Princess, a converted cruise ship.

Destination: Port Said, Egypt. There, the Americans

|

|

were segregated and along with

other collected ex-POWs yearning for home, took passage to Boston

on a Madson liner.

No more boxcars

and slop buckets. No more appelle (roll calls) in the pouring

rain and blowing snow. No more rotten cabbage soup nor latrine

trenches. No more lice-ridden straw mattresses. No more neins

and nyets.

Just miles

of majestic Douglas fir trees, stretching to the horizon....

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

HAPPY FEET! Hornbeck jumped

into Normandy wearing a pair of specialized boots identical to

these - available in 110 (!) different sizes. The fortified footwear

saved Len's feet when a German stick grenade exploded only inches

away. Corcorans** are still made and sold today - 69 years later,

and virtually unchanged except for the price - $120 a pair.

HAPPY FEET! Hornbeck jumped

into Normandy wearing a pair of specialized boots identical to

these - available in 110 (!) different sizes. The fortified footwear

saved Len's feet when a German stick grenade exploded only inches

away. Corcorans** are still made and sold today - 69 years later,

and virtually unchanged except for the price - $120 a pair.

Editor's note:

These combat boots were issued with a very rough suede like finish.

Nevertheless, within hours of issuing they had to be spit shined.

It was very difficult getting them to look this good. |

|

Len Hornbeck passed away in March 2014. His

memorial service was attended by 75 friends and relatives -- all

of whom were itching to stand up and reminisce about their departed

friend. A 15-foot table displayed his WW11 mementos from 70 years

ago. Len's widow Katherine held back her tears as she presented

each arriving mourner with a memorial booklet, the cover of which

displayed a descending paratrooper about to land on a German "potato

masher," or hand grenade. By any measure, Hornbeck was a

carbon copy poster boy of the perfect patriot, totally dedicated

to whatever task came his way. He never overcame the humiliation

which he silently suffered as a wounded prisoner of war -- not

because he felt sorry for himself, but because fate had denied

him the opportunity to test his resolve on the battlefield. A

dedicated logger all his working life, Len liked to claim that

he cut down half the old-growth Douglas fir forests in Washington

State before he quit the woods at age 70. Could it be that dodging

each falling mammoth was a victory in itself, thus filling the

void that troubled him so? In effect, did Leonard Hornbeck write

his own epitaph? It's not beyond the realm of possibility...

|

*Currahee

is a Cherokee Indian word meaning "Stands Alone," a phrase

which later became the Regiment's motto.

**Corcoran

Jumpboots were designed specifically for military parachute units during

WWII. They looked similar to combat boots.

| Tony Welch has

recorded oral histories of WW11 vets in seven states. His interest

in preserving first-person battlefield accounts began a half-century

ago, when as a U.S. Navy journalist he began "picking the

brains" of senior enlisted men. "If they had five or

more hash marks on their sleeve and campaign ribbons on their

chest, they were fair game," Welch says. |

Tony Welch |

Send Corrections, additions, and input to:

WebMaster/Editor

|