|

THE REAL

WORLD RECORD MUSKY

In

the waning days of 1942, an avid fisherman by the name of Louis

Spray forfeited his 1940 world record musky title, together with

all bragging rights. |

| Spray’s record catch was bested by

the United States Navy, when on December 13, l942 the fleet submarine

Muskallunge (SS-262) slid

down the ways at the Electric Boat Company in Groton, CT. The Muskallunge

– “musky” in angling lingo --numbered among an eventual 205 Gato/Balao

class submarines, joining earlier boats named after fresh water fish

such as Sturgeon, Perch, Pike, Trout, Bass

and Bluegill. Before war’s end the Bureau of Ships even found

room to squeeze in the Chub,

Dogfish and Carp. |

|

Muskallunge set

sail September 7, l943 from Pearl Harbor on the first of seven war

patrols. True to its namesake, the boat’s primary mission

was to lie in ambush undetected and wait for prey to enter her strike

zone. Including travel time, the average submarine patrol lasted

60-70 days and consumed 110,000 gallons of diesel fuel over the

course of 11,000 miles. Fewer than half the 85-man crew would see the sky until home port was reached at patrol’s

end.

The outbound Muskallunge held a bellyful of 24 “fish,” as the 3,000-pound torpedoes were labeled. Aboard were the very first electrically-driven torpedoes to be fired in combat. The electrics traveled at a modest 28 knots, but had the advantage of leaving no tell-tale surface turbulence in their wake, as did the earlier steam-driven projectiles which they gradually replaced. Still, faulty torpedoes plagued submarine skippers well into 1944. Many a Japanese vessel arrived safely in port displaying fender benders -- deeply dented hulls, clear evidence of a dud torpedo. Charles A. Kennedy, an electrician’s mate, helped commission Muskallunge and was aboard during the boat’s first two war patrols. |

Charles Kennedy helped commission Muskallunge and served aboard for two war patrols before transferring to Bergall (SS-320). Kennedy's pictured here at a 2003 Bergall reunion in Reno, Nevada, where 28 surviving crew members and their wives met to reminisce. WW11 "smokeboaters" (diesel engine sub crews) customarily wear vests adorned with colorful patches and decals to such gatherings. The names of the submarines they served aboard are displayed in large letters on the backs of the vests -- as one vet described it "....so we can easily spot a fellow crew member from one end of the bar to the other, despite our failing eyesight." Image courtesy USS Bergall.org |

“The

skipper on our first patrol was a sun worshipper,” recalls Kennedy,

now age 86 and a Camarillo, CA resident.

“Day after day he’d sit in a comforter chair topside, wearing

only shorts and sunglasses while reading a book and munching candy

bars as we cruised along.

“On this particular morning, one of the three bridge lookouts spotted a distant Japanese aircraft preparing to attack the boat. The diving klaxon sounded and everybody ran for the open hatch, including the captain. His sunglasses and cap went flying, his book and chair and candy bar went flying, so I’m told. And none of it was ever to be seen again. “At the time I was way aft in the maneuvering room,” Kennedy continues, “and noticed the propellers were making a commotion –- a very different sound. I happened to glance at the angle of dive indicator and noticed immediately the switch was on the wrong setting, so I ran over and reset the stern hydroplanes to speed up our rate of descent. Moments later a bomb exploded close overhead – it shook the boat badly and scared hell out of me. We continued down to about 200 feet when I heard my name shouted over the intercom – ‘Kennedy – report forward to the captain.’ Well, I got all puffed up – I was going to be complimented by the skipper. Maybe even get a medal on the spot for having saved the boat. Except I wasn’t wearing a shirt, so what would he pin it to? Maybe my bare chest…” |

| Kennedy continues: “I later learned that one of the mess cooks had got to poking around looking for certain food ingredients. Like all subs, we had food stashed in every possible nook and cranny and the mess cook thought he might |

‘"There's

room for everything on a submarine....except a mistake."

|

| have moved the control switch by accident.

So that’s what happened. But

the captain somehow concluded I had intentionally altered the switch

on the sly. And then while under attack, that I’d rushed over and

reset the controls so I could appear the hero who saved the day.”

Kennedy notes that none dared approach the captain with a plausible

explanation, adding that “…with all our ongoing engine troubles and

various electronic malfunctions, the captain gradually became more

and more distrustful of the crew. On more than one occasion he made that point

pretty clear, and in salty language we all understood.” |

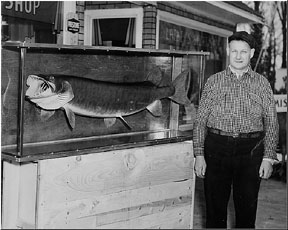

Leland D. White, CMoMM(SS) Leland White served as motor machinist mate aboard Muskallunge from launch to layup -- 40 months. Lee retired in 1960 -- a half-century ago -- as a chief petty officer after 23 years active duty. Post-war, he had duty tours on four other submarines. Now age 91 and active, he numbers among four known surviving crew members of Muskallunge. Image courtesy http://www.decklog.com |

Despite his bizarre encounter, Kennedy

is quick to note that the skipper went on to command other submarines,

and eventually retired a deeply tanned rear admiral. We asked Lee a burning question: were there any musky fishermen aboard the boat? |

| Hours before Durban Maru settled to the bottom, the

Japanese anti-submarine vessels began punishing Muskallunge with the first of more than 50 depth charges. The counter-attack went on intermittently for

eight hours. One or more “ashcans”

detonated close enough to the sub to cause serious leaks. “We tried sneaking off at a couple knots – no

good,” Lee recalls. “Their

sonar kept right on tracking us, even below 300 feet.

Lots of water accumulated in the aft engine compartment and

this extra weight slammed our stern into the ocean bottom, burying

the props. Finally we formed a bucket brigade and hauled

the water forward, then packed a bunch of the crew into the forward

torpedo room for added weight. And that’s how we finally broke the

stern free – rather like a teeter-totter.” A long voyage to Fremantle,

Australia followed, for repairs. |

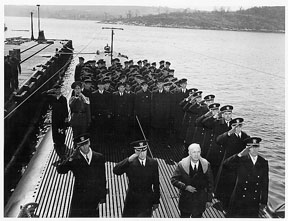

Muskallunge departs Pearl Harbor September 4, 1943 on her first war patrol. A year later, Musky narrowly escaped an 8-hour depth charge pounding after sinking a 7,160 ton transport off Cam Ranh Bay, French Indo-China. Aboard was a regiment of 3,000 Japanese soldiers, of whom 515 perished. (National Archives) |

A heavy fog blanketed the Sea of Japan that day. The radar range shortened until suddenly a cluster of three sea trucks came dimly into view. Selecting a target, Muskallunge commenced firing its main deck gun.

Muskallunge crew members monitor various shipboard controls during a shakedown cruise. Musky made her first war patrol in September 1943, taking station off the Palau Islands. The Gato-class submarine was decommissioned in 1947, then turned over to the Brazilian Navy and served a further 15 years as the Humanita." She ended her days as a practice target off Long Island NY in 1968." (National Archives) |

“My battle station was

to train this modified artillery piece,” Lee says. “Meaning, I maneuvered the gun horizontally

while the gun pointer to my left moved it vertically to get the weapon

on target. It was tough going because we kept poking in and out of

dense fog banks.” Higher up on the conning tower’s cigarette deck, electrician’s mate Chuck Whitman of Mayfield, N.Y. was busy manning a .50 caliber rail mounted machine gun. As the running battle progressed, several hits from the deck gun were observed. Then sudden return fire from one of the Japanese vessels struck Whitman, killing him instantly. Lee escaped the volley, while two nearby sailors received shrapnel wounds. The firefight was terminated, and later that day Whitman -- believed to be the last submariner to die in action during the war -- was buried at sea off the Kurile Islands in a brief ceremony. Three weeks later Muskallunge joined eleven other subs in Tokyo Bay for the formal surrender ceremonies ending World War Two. Muskallunge was decommissioned in 1947 and laid up for a few years, then loaned to the Brazilian Navy and returned in 1968. |

| “By pure chance a former

Muskallunge shipmate who was still on active duty, Val

Scanlon by name, happened to be at a Navy pier when the boat

came in and tied up,” Lee recalls. “He went aboard and it was a mess. Paint peeling off the bulkheads, trash everywhere.

Not the Muskallunge any of her old crew would ever care to see.” Steel ships, iron men. And a touch of irony. Three months later Scanlon was ordered to join a certain Atlantic fleet sub for temporary one-day duty. On July 9 the boat departed New London, CT and steamed to a Navy target practice area off Long Island, N.Y. In the distance, Scanlon spotted the submersible he’d helped commission a quarter-century earlier. Now the boat was empty, a derelict rolling in the ocean swells and straining at her anchor chain as though determined to get underway on her own.

|

|

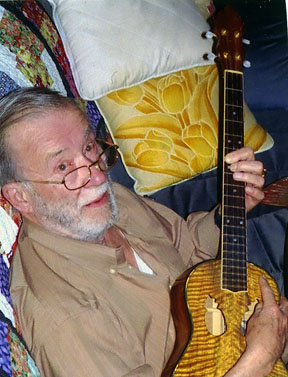

Tony Welch has recorded oral histories of WW11

vets in seven states. His interest in preserving first-person battlefield

accounts began a half-century ago, when as a U.S. Navy journalist

he began "picking the brains" of senior enlisted men.

"If they had five or more hash marks on their sleeve and campaign

ribbons on their chest, they were fair game," Welch says.

|