A fresh lieutenant in his '20s in those times, Hugh was one of those brash young American pilots, aircrew, and ground crews that came to England with their formidable B-17 and B-24 four-engine bombers in 1942 to join Britain in the war, along with their fighters and twin-engine bombers like the B-25 "Mitchell" and B-26 "Marauder". His bomber was nick-named the Southern Comfort, a "Flying Fortress" bristling with ten .50 calibre machine guns that stuck out like thorns all over the plane. Thorns that could send big bullets most of a mile. And bomb bays that could drop tons of destruction. The logo 'SOUTHERN COMFORT' was painted yellow over the olive drab of the plane, along with the 'wolf' motto of the squadron. The Southern Comfort became famous as she flew mission after mission from Chelveston. Each time, she brought her aircrew home. Even the last time--her 18th trip--the mortally wounded bomber got the crew back to England and all but one of them survived. I'm Trevor Williams, if I may introduce myself. I live in Wickford, part of Essex, England. That's a fair distance from the air base in Chelveston where Lt. Hugh Ashcraft and his American crew flew on missions to Germany and across Europe in the Second World War. But not so far from the grand old lady's resting place. I was part of the team that excavated pieces of the B17F Flying Fortress, number 4124617,WF*J, of the 305th Bomb Group 364th Bomb Squadron. We never disturb grave sites, by the way. We look only for the relics of war still buried in parts of England and many places in Europe and the Far East. I have many of those relics, and I cherish them. Sadly, there are many such "last flight" sites here. It may take 100 years or more to clear up the unexploded bombs, mines, bullets, and other remnants of that vast war, experts tell us. War leaves its mark. Even some small ponds today were once bomb craters. Or worse, craters left by exploded aircraft. There were also some other bombers and aircraft named Southern Comfort. They will be mentioned at the end of this article. Hugh wanted a momento, a piece of his beloved aircraft he had

named. I was there as host to see he got more than a rusty Coke

can as his fragment of history. I hoped each member of the crew

could have their own, but only Hugh came for his. Our search party moved to another place

around the wooded copse. This time the squall of the metal detector

was right on target. Hugh's fork clinked, and he turned up two

objects as thick as a thumb, heavy with brass and almost too long

to hold between thumb and forefinger. They were black-tipped .50

calibre "ball" machine gun rounds from the Southern

Comfort. This time Hugh's grin and laugh were pure delight. With

the dirt brushed off, the bullets were in remarkable condition,

shining in the sun. I don't think we will ever forget the look

on that man's face and the way he held those two .50 calibre rounds.

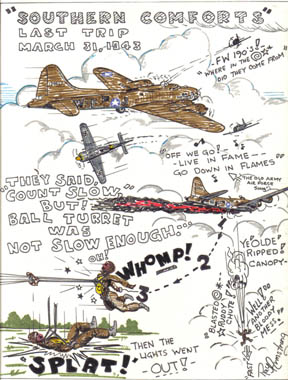

Mission planning called for the 364th of the "Can Do" and 303rd "Hell's Angels" bomb groups to join up. British fighters would escort the B-17's to a point just off the Dutch coast. Then the bombers would turn back. That's right. Not the fighters. While the bombers looped back toward England, the fighters would fly on to the target. Why? So the Brit fighters could meet and engage any enemy fighters before they attacked the bombers. This would force the enemy to burn fuel during the fight. They would have to break off and return to base for fuel, or so the plan went. During this fighter combat, the B-17's would turn around and fly toward Rotterdam docks again to drop their bombs. They should have a relatively easy time of it. Like most plans in war, this one lasted just long enough for contact with the enemy. pulled away. From the bottom ball turret, gunner Ray Armstrong noticed their number three engine was throwing oil spots on his view plate. He turned his turret so that James Patterson, flight engineer and waist gunner, could reach down through a hatch in the floor and wipe the oil off. As this was taking place, Armstrong looked back in shock to see three Focke-Wulf 190 German fighters flash past his tail. They came from above his right, went left, and banked around directly behind into the 6 o'clock firing position. No warning at all. "Fighters! 6 o'clock, diving low!" he yelled over the intercom. If anyone was dozing, they woke up fast. From a milk run, the flight turned into a nightmare in seconds. The FW-190's had hidden above the gray stratus clouds and jumped the bombers after they saw the escort fighters go on ahead, or so Ray Armstrong figured. He spun the ball turret forward to check 12 o'clock while tail gunner Frank Hilsabeck handled the fighters' rear attack at 6 o'clock . Armstrong's startled eyes saw four or five FW-190's headed toward him, low from the front. Something hit his turret. Then a liquid started to spray over it-- 100 octane aviation gasoline. A large hole appeared in the port underside wing between the number 1 and 2 engines, with a ruptured fuel tank hanging part way out of the hole and spraying gasoline. The first of the FW-190's from 11 o'clock opened up. Cannon fire hit the Southern Comfort in the bomb bay just in front of Armstrong's ball turret . Southern Comfort's bomb load was still aboard and armed. They hadn't made the bomb drop yet. Before Ray could react, the first FW-190 flashed by. The second one was a different story. Ray opened up with his twin .50 calibres about the same moment that the 190's weapons slammed into the bomber's underbelly. Hot lead from the .50's went into the 190's engine, which immediately exploded into flame as it went past. After seeing their buddy turn into a ball of fire, the other 190's broke away. But the bomber's leaking fuel also caught fire, making the inboard port wing a sheet of flame. All of this took place in less than three or four minutes. "There is nothing--absolutely nothing--that looks more awful than an aircraft in flames," Armstrong said. "Especially when you're in it."

Fighting the drag from the burning wing's

spoiled airflow, pilot Hugh broke from formation, leaving the

bomb run. The Southern Comfort raced back toward England, dropping

altitude. One part of the mission plan proved good. The German

fighter group JG-1 made only one pass in their Focke-Wulf 190's

because they were low on fuel, as expected. Thirty-three "heavies"

hit the dock area. The "Hell's Angel's" 303rd bomb group

missed and killed over 326 Dutch civilians. Doug Glover and Ray Armstrong made their way

bent over, back to the waist guns where James Patterson and Frank

Corser were putting on parachutes and checked each other's gear.

Top turret gunner Steve Gogolya also came back, rather than bail

out from the forward hatch. Tail gunner Frank Hilsabeck had his

own exit. Tail gunners were usually first out--and often the only

ones out--when a B-17 went down. All ten men were safely out of the burning plane, first tumbling and then 'chutes popped open into the vast sky. The Southern Comfort was alone now, trailing smoke and flame in a downward spiral. From brutal noise, all became quiet with only a hiss of wind. On the way down, Ray caught up with Frank Corser and began to pass him. "Hey, Corser," Ray yelled. "You're so small your 'chute is taking you back up!" Corser yelled back, "I'm not going up. You're going down...and fast." He pointed to Ray's parachute canopy. There was a large rip in the silk. That wasn't Armstrong's only problem. He looked

down to see that his doomed Southern Comfort had somehow made

it to England's coast, all right. Where? An airfield appeared

below the cloud cover along the coast, coming up at alarming speed.

The airfield was the RAF's Bradwell Bay. It was fully equipped

to repel enemy parachutists-- by having sharp invasion spikes

planted in the ground to skewer airborne troops. The last thing

Armstrong wanted was to be impaled like a stuck pig. Just before

he hit, he pulled the canopy partly below him as a cushion. As

he struck the ground, the lights went out. He regained consciousness

briefly to see two Royal Air Force types yelling abuse down on

him, then passed out again. Armstrong passed out a third time

in the X-ray department of a hospital before waking up in bed.

Lt. Hugh Ashcraft had better luck, coming down near the Essex village of Tollesbury in the mud flats. He also thought he might be impaled-- but by the masts of the fishing vessals lying at anchor. They missed him and the mud made for a soft landing. The local constable saw Lt. Ashcraft come down and took him to his own home, where Ashcraft had an "exceptional nice" cup of tea. His co-pilot Lt. Bill Lakey was dragged by his parachute through an open sewer drain outfall. Not a good smell. Lt. Lakey needed--and got--a hot bath and a change of clothes into a nice tweed jacket and trousers, thanks to local residents. Bob Nye was found in the home of the local doctor, and two of the crew were plucked from the River Blackwater by a new rescue launch just undergoing test trials. One crew member did not survive. Top turret

gunner Steve Gogolya, who had hestitated at being first out of

the waist gunners' door, had slipped out of his parachute harness

and died in the fall. A young woman picking wildflowers discovered

him at the base of a tree. His body was returned home to the U.S. I think the official figure is something

like 79,000 aircrew members who lost their lives flying from England.

The air museum at Duxford says 30,000 American lives were lost,

and the U.S. Adjutant General's office says 34,362 air corps personnel

were killed in action in the "Atlantic Region". ** What

I can tell you is this, there is a huge following over here in

England of enthusiasts who perpetuate and keep alive the memory

of those young men that came to England as part of the 8th and

9th USAAF. Nearly every former USAAF airfield has a memorial on

it or a museum which is usually housed in the former Watch Tower

(control tower). The movie "12 O' Clock High" opens

with a view of one of these old weed-grown airfields. In time, we recovered many other smashed and broken pieces, as well as .50 calibre ammunition. "John," I said to my companion,

"wouldn't it be nice if we could reunite the crew of the

Southern Comfort with her today?" We did not get all the crew back together

as we wanted. Some of them had visited the crash site during those

war years and got souvenirs of their own. Radio operator Doug

Glover sent us a real treasure he had picked up: part of the painted

yellow lettering on the metal nose. Just the OU from SOUthern

Comfort. He wrote that it belonged 'home' with the rest of the

aircraft. Retired Lt. Col. Hugh Ashcraft reported that Ray Armstrong died in 1984. Shortly after, Hugh was out mowing his lawn and suffered a heart attack. When the letter arrived on a Saturday morning telling of his death, I was numb and very emotional. He wasn't family, but someone who I could certainly call a wonderful friend. There were other aircraft named "Southern

Comfort" beside this one. Some with the nose art of a scantily-clad

young woman, giving a different meaning to Hugh's salute to the

Southern States of America. This particular crew was just ten men among thousands. During the many years I have been involved in this pastime, I have met many household names that will live in history--British, American, Polish, New Zealanders, Canadians, and Germans. All have one thing in common: they are ordinary human beings who went to fly and fight for their country. In writing about the Southern Comfort and her crew, I think it only right and fitting to dedicate these words in memory of top turret gunner Steve Gogolya. And to Hugh G. Ashcraft Jnr. and Ray Armstrong for the help I received during my research of their war, as well as the other members of the crew. God bless their memory and God bless America, to whom we all owe so very much in our continued fight for peace and freedom. END-------- Trevor

Williams could best be described as an aviation archeologist. He

is a WWII aircraft recovery specialist. Trevor is historian, researcher,

hands-on digger, and public speaker. He helped find and recover

parts of about 40 airplanes that went down in England, France, and

elsewhere during that war. Many of those relics went to museums. ** This is a correction. See Volume 7, Letters or to go directly directly click here. Send Corrections, additions, and input to: |