|

My World War II Heroes - A Daughter's Memoir By: Sue Townley Monkress Dedicated to the

American Soldier

War is indescribable hell. It gnaws;

it violently wrenches the souls from many. In spite of the horror, the

sometimes utter confusion and paralyzing fear during WWII, our soldiers

did their jobs - whether they enlisted voluntarily or were drafted to

service. There are so many stories, about the men and women from - as

Tom Brokaw aptly describes: "The Greatest Generation." These

heroes grew up at a time when the world was in crisis. They freed not

only Europe from the tyranny of a madman, but possibly halted what could

have been the demise of democracy. Meanwhile, Clarence ("Eddie" to most in those days) was enlisting in the army in Kansas, (April 8, 1943). When he last kissed his girlfriend back in Atwood, she wouldn't learn until later that he was leaving for service in the Glider Infantry Regiment of the Army. For three years, letters would be these lovebirds' only communication. Virgil, hating farm work back in Oklahoma and after an unfortunate row with his Father, left home to escape the farm. After his draft, he flirted with the idea that he might make a career with Uncle Sam. Little did he know he'd deal with a lot worse than plowing - but instead, the hells of three wars; and all the while struggling to raise his family. ~

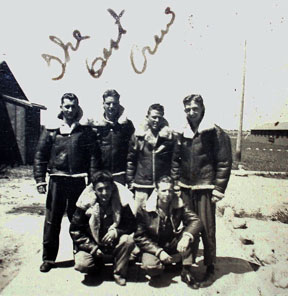

WAR JOURNAL - October 2, 1943. (Private

John Haggarty of the 533rd Bombardment Squadron, 381st Bombing Group,

located in Ridgewell, England): "Six new combat crewmen assigned:

T/Sgt Edward J. Senk, Melvin A. Soderstrom, S/Sgts Frank P. Mitchley,

John F. Skrapits, Leburn W. Townley, John E. Miskin."

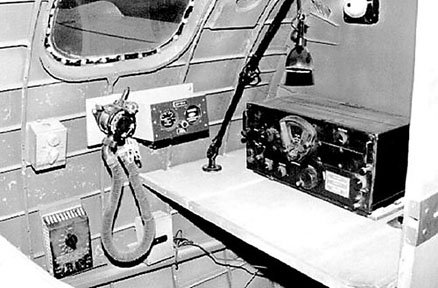

Boeing produced the bomber in small numbers in the late thirties and sub-contracted with Lockheed-Vega factories to produce later models of the B-17 during the height of the conflict. They were able to supply over 3,400 of the "F" model and over 8,600 of the "G" model. Some models were equipped with lifeboats for sea rescues but the primary use of the planes was the raids on European targets. One of the most famous of these planes, The Memphis Bell, was able to complete twenty-five bombing missions over European territory.

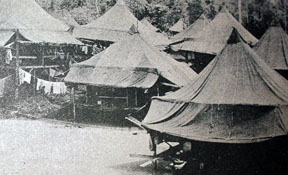

~ Meanwhile, on a tropical excursion in New Guinea after a "cruise" on a crowded luxury liner from the States, Virgil (who later became my beloved Step-Dad) languished in the bright sunshine. Uh … let's try that again: he tromped through … mud. Mud, mud and more MUD. "New Guinea, thy name is mud!" The guys he served with later wrote: "any picture not showing the abundant supply of that material … wasn't authentic." The rain came only once a year, but it stayed 365 days, which made living pretty miserable -- clothes wouldn't dry; mosquitoes ate them alive.The military posted billboards reminding them to take their drugs for malaria and other sundry ills. And … despite the travel brochures they'd read, depicting: 'an island paradise with obliging and stunning native women,' these boys were in for quite a surprise upon arrival. Virgil, being the gentleman he was, wouldn't even comment on the sight of the 'beautiful' native women he'd heard about. Albeit to say … he and all his buddies only dreamed of the sweet-looking, sweet-smelling American girls back home. He later told me that when he arrived in New Guinea from the ship, they ran fifteen to twenty smaller boats of troops for three days to unload men and supplies. He could view Australia across the bay. When they first arrived, it was quiet for awhile. The troops walked about a mile through knee-deep mud and another half mile to the camp, where he viewed about a hundred tents. When he looked west, he said he saw the top of a mountain with a beautiful building - General McArthur's headquarters. But he never knew whether the General was there. He and his seven-man crew walked from one side of the island to the other, to the peninsula, and set up positions. They once unknowingly passed under a lone Japanese soldier, spying in coconut trees. Virgil believed "that Jap in the tree could have killed him a dozen times; he'd watched me set up all day and never once fired - amazing!" When he was finally discovered, they "just told the Japanese soldier to come on down" and kept him as a prisoner. The Japanese had installed booby-traps everywhere, with strings attached to hand grenades. Walking gingerly, Virgil set up his 50-caliber machine gun, dug a foxhole, and began surveillance out at the sea from his position. The troops routinely used anti-aircraft fire to down Japanese planes. At times, they also fought off an unexpected boatload of arriving enemy. One time, while practicing "landings," they walked through a field full of Japanese bodies. He said he inadvertently stepped on a dead soldier, rotting and smelling, the body fluids splashing up on him. Though he tried washing off his clothes and putting them back on, he said he smelled a month. Virgil spent a year at this location, as a "Machine Gun Sergeant, or Buck Sergeant" before moving north to Luzon and then to Manilla Bay in the Philippines. He described looking north out of Manilla, on top of a mountain was a big, dark cross. Said it was "a monsterous size - could see it for a mile." I wonder if he stared a lot at that cross; it must have been a comfort. A young man named Lackernick from Hackinsack, New Jersey, became a close friend. They had a big, tough captain from Texas as a commander and went around on small LST's (landing ship tanks), checking the beach. Their captain kept them pumped up for action, yet lightened things a bit with a weekly, five-gallon kiln of homemade booze. Each of the guys had a canteen cup and the captain would pour them a drink at dinner. They all played jokes on each other, but at night it was "all quiet, no lights." Virgil drew me a descriptive image about a Japanese pilot they called "Washing Machine Charlie," who buzzed them often in a small, noisy plane. He threw out personnel bombs, a foot long, by hand, "like he was scattering apples." Throughout the night, all they could see was the plane's lights, his psychological warfare keeping them awake and rattled. These details gave me some thought-provoking images, redefining my definition of "incoming!" Virgil said the shelling was "loud and scary, but you were just too busy to worry at the time." But, if they weren't worried about defending against the enemy, I would imagine the isolation was a major contributor to their angst. Virgil remained in the Philippines until the end of the war. He made First Sergeant rank within three years. Seven in his battalion were killed. ~ At least Lee, flying in and out of London, had occasional leave. And … enough for this rakish rogue to form a sparky acquaintance with a pretty lass named Jean in rural England. He would later tell my brothers and me stories about necking (kissing) with Miss Jean, while riding separate bicycles down country roads. That must have commanded a bit of navigational skill! Dad also had the opportunity to do a bit of sight-seeing, but his description of those "castles": he wasn't impressed with the "titled." Said most of them were actually very small. Taking a quote from Shakespeare, seemed like "much ado about nothing" to him. I'm sure it was harder to leave fair Jean than the castles of England. I must admit, for awhile, I had a bit of trouble with this particular information. But after time and thoughtful contemplation, I became grateful he'd acquired a sweet friend to pleasantly occupy his thoughts, giving him occasional respite during this terrible time in his life. And … he was later rewarded by marrying a fiery Irish-American redhead named Betty Jo - my beautiful Mother. ~ "Alright, buddy, get ready. We're gonna send you on out and you'll be released soon." No, that wasn't the coveted discharge orders from military duty; it was an officer's instructions right before Clarence (Eddie), my Dad-in-law, was pulled down into Belgium in a glider. He just prayed he'd not encounter any krauts down below with guns already fixed on them … Sorry, Eddie, no such luck. Eddie served in the 17th Airborne Division

from 1944 to 1945. Their shoulder patch had a circle with black background

upon which is an outstretched eagle's talon in gold. The colors suggested

seizing the golden opportunity by the surprise with which airborne operations

were carried out. Their motto: "Thunder from Heaven."

Unfortunately, we didn't talk about this, so don't know many details, but these facts in themselves tell a vivid story of how frantic the action must have been! Sadly, all four were awarded posthumously. ~

Dad would later, (reluctantly) tell me stories of seeing men killed by enemy fire, right in front of him. Nearly every trip resulted in their B-17 returning, riddled in lacy designs by German bullets. Aluminum and plexiglass presented little barrier to bullets or flak shrapnel. Dad agonizingly described once witnessing a crew member catch a startling chainsaw-like spray of bullets through the plane, slicing off the top portion of that man's head. The soldier wasn't a member of their regular crew; he was a one-time fill-in for a tail gunner. Seems so very sad -- like the luck of a bad draw. Dad related how once the top piece on their plane came loose and a crew member had hold of it, trying to secure it back down, but the man was sucked out the opening. There were several occasions, after moving forward a bit to relay information to his pilot, Dad backed into his seat, noticing the fresh bullet holes right at the position his own head would have been. If he hadn't moved at that particular moment, he would have experienced the same fate as his crew member. Fate brought my father home. Lucky for me. That same fate brought me into this world; otherwise, I surely wouldn't be writing this now. Many of his friends were not so lucky. WAR JOURNAL: Dec'43: "Nine ships

from this squadron were part of the formation, the pilots participating

were: Lts Gleichauf, Butler, Chason, Crozier, Parsons, Nason, Fridgen,

Klein and Stewart Hanson. Radio operator S/Sgt Curtis E. Hickman

died of anoxia on the return trip. His body was taken to the 121st Station

Hospital at Braintree, a few miles away." A statistic I found compelling: more U.S. servicemen died in the Air Corps than the Marine Corps. While completing the required thirty missions in bomber planes, the chance of being killed was seventy-one percent. The last time Dad climbed aboard a military plane was to return to his base in Oklahoma. Upon 'landing,' the small plane flipped over, sliding down the runway, eventually stopping upside-down. Fortunately, the crew all walked away from it. I believe he felt he'd tempted Fate enough - he never stepped foot in an airplane again. He passed away several years ago and my brothers and I miss 'His Orneryness' still. ~ My Step-Dad, Virgil, not only successfully completed his Pacific tour during WWII, but also directed other men in the Korean War and Vietnam conflict. He retired in 1973 after nearly three decades of service. Due to his military experiences, he is very organized and disciplined. Amazingly, after witnessing the horrors of three wars -- the indescribable sounds and smells of death, my step-Dad is also a very compassionate, kind and giving man. Most of what I've compiled here, he related to me earlier. He currently is experiencing some memory losses and I hope that if he forgets anything about his military career, it's the violent, unhappy memories; not his brave buddies and their camaraderie. ~ Eddie, (my Dad-in-law) returned and married his girlfriend, Fera, in Kansas -- another beautiful redhead. He always seemed to have handled his war experiences fairly well; I suppose that was due to being quite pragmatic about it. I believe he felt that it does no good to dwell in guilt. He and his buddies simply did their job, and came home. Though he has also passed on and is missed by his family, his military legacy continued in his sons and grandsons. It's amazing to me how so many young men (and women) can go off on missions such as these, witness the atrocities that routinely come with war effort, perform a valiant job, and then wearily return home. They're then expected to re-ingratiate themselves into normal lives, into a public that has no base, absolutely no comprehension of what they experienced. I remember seeing old news clips and pictures showing the excitement at reports of the end of the war: the jubilation and partying - sailors grabbing girls and kissing them enthusiastically. And the gals (whether they knew them or not), seemingly responding in-kind. What wonderful news for a weary nation! But though we've seen many romantic images of the war's end, I don't believe it really ended so quickly for the weary participants. Once returning, none of these three men talked much of the war. I've heard lots of other family members say that same thing about their soldiers. They had their memories, their nightmares, but mostly kept those to themselves. Regretfully, I often wish I had asked my Dads more about their experiences, especially since I am now endeavoring to write them down. But, on the other hand, perhaps some of the memories would have been too painful for them to revisit very thoroughly. Of necessity, they made fast friends, but those they lost were a sad reminder. Even though they were all heroes in my eyes, I wonder whether they and many of their comrades felt unworthy to have survived, when so many of their buddies did not. Four-hundred and forty Medals of Honor were awarded during WWII. Sorrowfully, two-hundred fifty of those were awarded posthumously. I'm sure there should have been other medals presented; not all valiant action could be reported. We're losing these valiant heroes at a rapidly-increasing pace. Therefore, we can't praise these Americans enough - for the sacrifices they made to ensure the continuance of our country's democracy and the freedom we enjoy. And not only those from World War II, but we must honor all soldiers, sailors, air force and marines (both men and women) from every war this country has engaged in. Like his grandfathers in World War II and his

father in Vietnam, my younger son has experienced two Seabee deployments

in hostile confrontations: in Iraq and Afghanistan. Each time I anguish

until he returns. He currently is deployed on another nearly year-long

overseas assignment, leaving his wife, two children and a third on the

way. Godspeed, my son. Acknowledgements/Sources:

|

![]()

Send Corrections, additions, and input to:

|

Visitors since

June 6, 2000 |