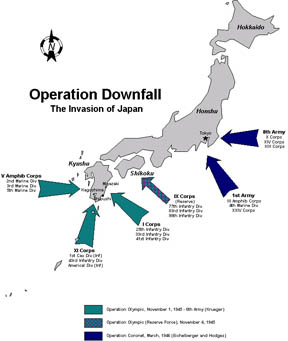

Map courtesy US Army Corps of Engineers Click Image for a larger view (It will come up in a new window so you can keep it handy for reference) |

An Invasion Not Found in the History Books

|

Deep in the recesses

of the National Archives in Washington,D.C., hidden for nearly four decades

lie thousands of pages of yellowing and dusty documents stamped "Top

Secret". These documents, now declassified, are the plans for Operation

Downfall, the invasion of Japan during World War II. Only a few Americans

in 1945 were aware of the elaborate plans that had been prepared for the

Allied Invasion of the Japanese home islands. Even fewer today are aware

of the defenses the Japanese had prepared to counter the invasion had

it been launched. Operation Downfall was finalized during the spring and

summer of 1945. It called for two massive military undertakings to be

carried out in succession and aimed at the heart of the Japanese Empire.

In the first invasion - code named Operation Olympic - American

combat troops would land on Japan by amphibious assault during the early

morning hours of November 1, 1945 - 50 years ago. Fourteen combat divisions

of soldiers and Marines would land on heavily fortified and defended Kyushu,

the southernmost of the Japanese home islands, after an unprecedented

naval and aerial bombardment.

|

With

the exception of a part of the British Pacific Fleet, Operation

Downfall was to be a strictly American operation.

|

The second invasion on March 1, 1946 - code named Operation Coronet - would send at least 22 divisions against 1 million Japanese defenders on the main island of Honshu and the Tokyo Plain. It's goal: the unconditional surrender of Japan. With the exception of a part of the British Pacific Fleet, Operation Downfall was to be a strictly American operation. It called for using the entire Marine Corps, the entire Pacific Navy, elements of the 7th Army Air Force, the 8 Air Force (recently redeployed from |

| Admiral

William Leahy estimated that there would be more than 250,000 Americans

killed or wounded on Kyushu alone. General Charles Willoughby, chief

of intelligence for General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander

of the Southwest Pacific, estimated American casualties would be one

million men by the fall of 1946. Willoughby's own intelligence staff

considered this to be a conservative estimate. During the summer of 1945, America had little time to prepare for such an endeavor, but top military leaders were in almost unanimous agreement that an invasion was necessary. While naval blockade and strategic bombing of Japan was considered to be useful, General MacArthur, for instance, did not believe a blockade would bring about an unconditional surrender. The advocates for invasion agreed that while a naval blockade chokes, it does not kill; and though strategic bombing might destroy cities, it leaves whole armies intact. So on May 25, 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, after extensive deliberation, issued to General MacArthur, Admiral Chester Nimitz, and Army Air Force General Henry Arnold, the top secret directive to proceed with the invasion of Kyushu. The target date was after the typhoon season. |

General Douglas MacArthur estimated American casualties would be one million men by the fall of 1946 (National Archives) |

|

President Truman approved

the plans for the invasions July 24. Two days later, the United

Nations issued the Potsdam Proclamation, which called upon Japan

to surrender unconditionally or face total destruction. Three days

later, the Japanese governmental news agency broadcast to the world

that Japan would ignore the proclamation and would refuse to surrender.

During this sane period it was learned -- via monitoring Japanese

radio broadcasts -- that Japan had closed all schools and mobilized

its schoolchildren, was arming its civilian population and was fortifying

caves and building underground defenses.

Operation Olympic called for a four pronged assault on Kyushu. Its purpose |

The preliminary invasion would began October 27 when the 40th Infantry Division would land on a series of small islands west and southwest of Kyushu. At the same time, the 158th Regimental Combat Team would invade and

| occupy a small island 28 miles south of Kyushu. On these islands, seaplane bases would be established and radar would be set up to provide advance air warning for the invasion fleet, to serve as fighter direction centers for the carrier-based aircraft and to provide an emergency anchorage for the invasion fleet, should things not go well on the day of the invasion. As the invasion grew imminent, the massive firepower of the Navy - the Third and Fifth Fleets -- would approach Japan. The Third Fleet, under Admiral William "Bull" Halsey, with its big guns and naval aircraft, would provide strategic support for the operation against Honshu and Hokkaido. Halsey's fleet would be composed of battleships, heavy cruisers, destroyers, dozens of support ships and three fast carrier task groups. From these carriers, |

Admiral William "Bull" Halsey |

Hellcat folding wings on carrier (Nat'l Archives) |

Several days before the invasion, the battleships, heavy cruisers and destroyers would pour thousands of tons of high explosives into the target areas. They would not cease the bombardment until after the land forces had been launched. During the early morning hours of November 1, the invasion would begin. Thousands of soldiers and Marines would pour ashore on beaches all along the eastern, southeastern, southern and western coasts of Kyushu. Waves of Helldivers, Dauntless dive bombers, Avengers, Corsairs, and Hellcats from 66 aircraft carriers would bomb, rocket and strafe enemy defenses, gun emplacements and troop concentrations along the beaches. |

The Eastern Assault Force consisting of the 25th, 33rd and 41st Infantry Divisions would land near Miyaski, at beaches called Austin, Buick, Cadillac, Chevrolet, Chrysler, and Ford, and move inland to attempt to capture the city and its nearby airfield. The Southern Assault Force, consisting of the 1st Cavalry Division, the 43rd Division and Americal Division would land inside Ariake Bay at beaches labeled DeSoto, Dusenberg, Ease, Ford, and Franklin and attempt to capture Shibushi and the city of Kanoya and its airfield.

On the western shore of Kyushu, at beaches Pontiac, Reo, Rolls Royce, Saxon, Star, Studebaker, Stutz, Winston and Zephyr, The V Amphibious Corps would land the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Marine Divisions, sending half of its force inland to Sendai and the other half to the port city of Kagoshima.

On November 4, the Reserve Force, consisting of the 81st and 98th Infantry Divisions and the 11th Airborne Division, after feigning an attack of the island of Shikoku, would be landed -- if not needed elsewhere -- near Kaimondake, near the southernmost tip of Kagoshima Bay, at the beaches designated Locomobile, Lincoln, LaSalle, Hupmobile, Moon, Mercedes, Maxwell, Overland, Oldsmobile, Packard and Plymouth.

Olympic was not just a plan for invasion, but for conquest and occupation as well. It was expected to take four months to achieve its objective, with the three fresh American divisions per month to be landed in support of that operation if needed.

If all went well with Olympic, Coronet would be launched March 1, 1946. Coronet would be twice the size of Olympic, with as many as 28 divisions landing on Honshu.

All along the coast east of Tokyo, the American 1st Army would land the 5th, 7th, 27th, 44th, 86th, and 96th Infantry Divisions along with the 4th and 6th Marine Divisions.

At Sagami Bay, just south of Tokyo, the entire 8th and 10th Armies would strike north and east to clear the long western shore of Tokyo Bay and attempt to go as far as Yokohama. The assault troops landing south of Tokyo would be the 4th, 6th, 8th, 24th, 31st, 37th, 38th and 8th Infantry Divisions, along with the 13th and 20th Armored Divisions.

| Following the initial assault, eight more divisions - the 2nd, 28th, 35th, 91st, 95th, 97th and 104th Infantry Divisions and the 11th Airborne Division -- would be landed. If additional troops were needed, as expected, other divisions redeployed from Europe and undergoing training in the United States would be shipped to Japan in what was hoped to be the final push. |

... other divisions redeployed

from Europe and undergoing training in the United States would be

shipped to Japan

|

Captured Japanese documents and post war interrogations of Japanese military leaders disclose that information concerning the number of Japanese planes available for the defense of the home islands was dangerously in error.

During the sea battle at Okinawa alone, Japanese kamakaze aircraft sank 32 Allied ships and damaged more than 400 others. But during the summer of 1945, American top brass concluded that the Japanese had spent their air force since American bombers and fighters daily flew unmolested over Japan.

What the military leaders did not know was that by the end of July the Japanese had been saving all aircraft, fuel, and pilots in reserve, and had been feverishly building new planes for the decisive battle for their homeland.

|

As part of Ketsu-Go, the name for the plan

to defend Japan -- the Japanese were building 20 suicide takeoff

strips in southern Kyushu with underground hangars. They also had

35 camouflaged airfields and nine seaplane bases. The Japanese had 58 more airfields in Korea, western Honshu and Shikoku, which also were to be used for massive suicide attacks. Allied intelligence had established that the Japanese had no more than 2,500 aircraft of which they guessed 300 would be deployed in suicide attacks. |

|

Additionally, the Japanese were building newer and more effective models of the Okka, a rocket-propelled bomb much like the German V-1, but flown by a suicide pilot. When the invasion became imminent, Ketsu-Go called for a fourfold aerial plan of attack to destroy up to 800 Allied ships. While Allied ships were approaching Japan, but still in the open seas, an initial force of 2,000 army and navy fighters were to fight to the death to control the skies over Kyushu. A second force of 330 navy combat pilots were to attack the main body of the task force to keep it from using its fire support and air cover to protect the troop carrying transports. While these two forces were engaged, a third force of 825 suicide planes was to hit the American transports. As the invasion convoys approached their anchorages, another 2,000 suicide planes were to be launched in waves of 200 to 300, to be used in hour by hour attacks. By mid-morning of the first day of the invasion, most of the American land-based aircraft would be forced to return to their bases, leaving the defense against the suicide planes to the carrier pilots and the shipboard gunners. Carrier pilots crippled by fatigue would have to land time and time again to rearm and refuel. Guns would malfunction from the heat of continuous firing and ammunition would become scarce. Gun crews would be exhausted by nightfall, but still the waves of kamikaze would continue. With the fleet hovering Japanese planned to coordinate their air strikes with attacks from the 40 remaining submarines from the Imperial off the beaches, all remaining Japanese aircraft would be committed to nonstop suicide attacks, which the Japanese |

Were the aircraft really there? With regard to the 12,700 Japanese aircraft available to strike our Army and Navy forces. I would like to tell you of my first hand encounter with the so called strike force. When I flew into Miazuguhara Air Force Base in Kumigaya, Japan on 6 September 1945, I together with Agents of the 441 CIC Detachment found over two thousand new Japanese military aircraft of various types bombers, fighters etc. The only problem they were only fuselages, not a single engine anywhere to be found Upon concentrated investigation it was determined Japan was unable to produce the raw materials to build any engines. Interesting, they had thousands of airplanes that couldn't fly. Fred Waterhouse 3-07-07 Editor's not: Fred was a Counter Intelligence Corps agent who had a specialty background in investigating aircraft accidents for sabotage, etc. An interesting comment! |

The Imperial Navy had 23 destroyers and two cruisers which were operational. These ships were to be used to counterattack the American invasion. A number of the destroyers were to be beached at the last minute to be used as anti-invasion gun platforms.

Once offshore, the invasion fleet would be forced to defend not only against the attacks from the air, but would also be confronted with suicide attacks from sea. Japan had established a suicide naval attack unit of midget submarines, human torpedoes and exploding motorboats

|

The goal of the Japanese was to shatter the invasion before the landing. The Japanese were convinced the Americans would back off or become so demoralized that they would then accept a less-than-unconditional surrender and a more honorable and face-saving end for the Japanese. See Trinity for more on this! |

The goal of the Japanese was to shatter the invasion before the landing. The Japanese were convinced the Americans would back off or become so demoralized that they would then accept a less-than-unconditional surrender and a more honorable and face-saving end for the Japanese. But as horrible as the battle of Japan would be off the beaches, it would be on Japanese soil that the American forces would face the most rugged and fanatical defense encountered during the war. |

Throughout the island-hopping Pacific campaign, Allied troops had always out numbered the Japanese by 2 to 1 and sometimes 3 to 1. In Japan it would be different. By virtue of a combination of cunning, guesswork, and brilliant military reasoning, a number of Japan's top military leaders were able to deduce, not only when, but where, the United States would land its first invasion forces.

Facing the 14 American divisions landing at Kyushu would be 14 Japanese divisions, 7 independent mixed brigades, 3 tank brigades and thousands of naval troops. On Kyushu the odds would be 3 to 2 in favor of the Japanese, with 790,000 enemy defenders against 550,000 Americans. This time the bulk of the Japanese defenders would not be the poorly trained and ill-equipped labor battalions that the Americans had faced in the earlier campaigns.

| The Japanese defenders would be the hard core of the home army. These troops were well-fed and well equipped. They were familiar with the terrain, had stockpiles of arms and ammunition, and had developed an effective system of transportation and supply almost invisible from the air. Many of these Japanese troops were the elite of the army, and they were swollen with a fanatical fighting spirit. |

The Japanese defenders would be the hard core

of the home army. These troops were well-fed and well equipped.

|

Japan's network of beach defenses consisted of offshore mines, thousands of suicide scuba divers attacking landing craft, and mines planted on the beaches. Coming ashore, the American Eastern amphibious assault forces at Miyazaki would face three Japanese divisions, and two others poised for counterattack. Awaiting the Southeastern attack force at Ariake Bay was an entire division and at least one mixed infantry brigade.

On the western shores of Kyushu, the Marines would face the most brutal opposition. Along the invasion beaches would be the three Japanese divisions , a tank brigade, a mixed infantry brigade and an artillery command. Components of two divisions would also be poised to launch counterattacks.

If not needed to reinforce the primary landing beaches, the American Reserve Force would be landed at the base of Kagoshima Bay November 4, where they would be confronted by two mixed infantry brigades, parts of two infantry divisions and thousands of naval troops.

All along the invasion beaches, American troops would face coastal batteries, anti-landing obstacles and a network of heavily fortified pillboxes, bunkers, and underground fortresses. As Americans waded ashore, they would face intense artillery and mortar fire as they worked their way through concrete rubble and barbed-wire entanglements arranged to funnel them into the muzzles of these Japanese guns.

| On the beaches and beyond would be hundreds of Japanese machine gun positions, beach mines, booby traps, trip-wire mines and sniper units. Suicide units concealed in "spider holes" would engage the troops as they passed nearby. In the heat of battle, Japanese infiltration units would be sent to reap havoc in the American lines by cutting phone and communication lines. Some of the Japanese troops would be in American uniform, English-speaking Japanese officers were assigned to break in on American radio traffic to call off artillery fire, to order retreats and to further confuse troops. Other infiltration with demolition |

Beyond the beaches were large artillery pieces situated to bring down a curtain of fire on the beach. Some of these large guns were mounted on railroad tracks running in and out of caves protected by concrete and steel.

| The battle for Japan would be won by what Simon Bolivar Buckner, a lieutenant general in the Confederate army during the Civil War, had called "Prairie Dog Warfare." This type of fighting was almost unknown to the ground troops in Europe and the Mediterranean. It was peculiar only to the soldiers and Marines who fought the Japanese on islands all over the Pacific -- at Tarawa, Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Prairie Dog Warfare was a battle for yards, feet and sometimes inches. It was brutal, deadly and dangerous form of |

The battle for Japan would be

won by what Simon Bolivar Buckner, a lieutenant general in the Confederate

army during the Civil War, had called "Prairie Dog Warfare."

|

|

In the mountains behind the Japanese beaches were underground networks of caves, bunkers, command posts and hospitals connected by miles of tunnels with dozens of entrances and exits. Some of these complexes could hold up to 1,000 troops. In addition to the use of poison gas and bacteriological warfare (which the Japanese had experimented with), Japan mobilized its citizenry. Had Olympic come about, the Japanese civilian population, inflamed by a national slogan - "One Hundred Million Will Die for the Emperor and Nation" - were prepared to fight to the death. Twenty Eight Million Japanese |

|

At the early stage of the invasion, 1,000 Japanese and American soldiers would be dying every hour The invasion of Japan never became a reality because on August 6, 1945, an atomic bomb was exploded over Hiroshima. Three days later, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Within days the war with Japan was at a close. |

At the early stage of the invasion, 1,000 Japanese

and American soldiers would be dying every hour.

|

Had these bombs not been dropped and had the invasion been launched as scheduled, combat casualties in Japan would have been at a minimum of the tens of thousands. Every foot of Japanese soil would have been paid for by Japanese and American lives.

One can only guess at how many civilians would have committed suicide in their homes or in futile mass military attacks.

In retrospect, the 1 million American men who were to be the casualties of the invasion, were instead lucky enough to survive the war.

Intelligence studies and military estimates made 50 years ago, and not latter-day speculation, clearly indicate that the battle for Japan might well have resulted in the biggest blood-bath in the history of modern warfare.

Far worse would be what might have happened to Japan as a nation and as a culture. When the invasion came, it would have come after several months of fire bombing all of the remaining Japanese cities. The cost in human life that resulted from the two atomic blasts would be small in comparison to the total number of Japanese lives that would have been lost by this aerial devastation.

|

Japan today could be divided

much like Korea and Germany.

|

With American forces locked in combat in the south of Japan, little could have prevented the Soviet Union from marching into the northern half of the Japanese home islands. Japan today could be divided much like Korea and Germany. |

The world was spared the cost of Operation Downfall, however, because Japan formally surrendered to the United States September 2, 1945, and World War II was over.

The aircraft carriers, cruisers and transport ships scheduled to carry the invasion troops to Japan, ferried home American troops in a gigantic operation called Magic Carpet.

In the fall of 1945, in the aftermath of the war, few people concerned themselves with the invasion plans. Following the surrender, the classified documents, maps, diagrams and appendices for Operation Downfall were packed away in boxes and eventually stored at the National Archives. These plans that called for the invasion of Japan paint a vivid description of what might have been one of the most horrible campaigns in the history of man. The fact that the story of the invasion of Japan is locked up in the National Archives and is not told in our history books is something for which all Americans can be thankful.

![]() Epilog

Epilog

I had the distinct privilege of being assigned as later commander of the 8090th PACUSA detach, 20th AAF, and one of the personal pilots of then Brig General Fred Irving USMA 17 when he was commanding general of Western Pacific Base Command. We had a brand new C-46F tail number 8546. It was different from the rest of the C-46 line in that it was equipped with Hamilton Hydromatic props whereas the others had Curtis electrics. On one ofthe many flights we had 14 Generals and Admirals aboard on an inspection trip to Saipan and Tinian. Notable aboard was General Thomas C. Handy, who had signed the operational order to drop the atomic bombs on Japan. President Truman's orders were verbal . He never signed an order to drop the bombs. On this particular flight, about halfway from Guam to Tinian, a full Colonel (General Handy's aide) came up forward and told me that General Handy would like to come up and look around. I told him, Hell yes, he can fly the airplane if he wants to, sir

| He came up and sat in the copilot's seat, put on the headset and we started chatting. I asked him if he ever regretted dropping the bombs. His answer was, Certainly not. We saved a million lives on both sides by doing it. It was the right thing to do I never forgot that trip and the honor of being able to talk to General Handy. I was a Lt at the time. A postscript |

"I asked him if he ever regretted dropping

the bombs. His answer was, Certainly not. We saved a million lives

on both sides by doing it."

|

I am very happy the invasion never came off because if it had I don't think I would be writing this today. We were to provide air support for the boots on the ground guys. The small arms fire would have been devastating and lethal as hell to fly through .. Just think what it would have been like on the ground .....

But, C'est !a vive. You do what needs to be done. You don't act like gutless wonders and carry peace signs around ....

![]()

"Of course we celebrated (the bombing if Hiroshima.) We were fully aware that our death sentence had been lifted."

Major General Will Simlik, USMC (ret)

Suggested by Tom Kercher and John Hopkins

Did You Know?

Army Engineers Were a Critical Part of the

Greatest Invasion that Never Was? Click the star to read their part:

Send Corrections, additions,

and input to:

|

Visitors since

June 6, 2000 |