Jackson, CampClinton

|

|

|

|

|

|

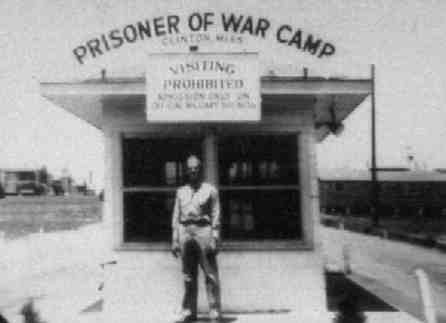

"Everyone came out from town to look at the dreaded enemy but all they found were some lonesome boys just like our own." said Marion Rogers Wells, civilian nurse at camp. This is typical of the responses from everyone that was there — German and American. Three nurses, several other veterans, as well as newspaper clippings reveal a continuing fondness from both sides about the place and the people. It just wasn't what you would expect from a prisoner of war camp. I went there expecting pictures of a grim gray place with barbed wire and guard towers. The only picture I found that was reminiscent of this was one picture with the prisoners all lined up as if to hear the Kommandant threaten to shoot escapees.

|

|

|

It turned out to be a mustering of all hands to receive intra mural sports awards. Prisoners organized a jazz band, theatrical group and a symphony orchestra. The prisoners, if they chose to work, were paid eighty cents a day which was deposited in their own "kanteen." So you saw young "boys" walking around sipping pop. If they chose, they could wear their own uniform if they didn't feel right wearing GI uniforms with "PW" in large white letters on their back. A well-equipped hospital was enclosed within the compound. The prisoners received the same care as the Americans.

"We had only one MP to guard us at night and he didn't even have a gun, just a club. I drove around in the compound at night in a jeep and no one ever bothered me. Some seemed very cultured and some didn't but they were always polite. One even had a crush on me but I didn't find out about for 50 years." Marion Rogers Wells, civilian nurse at camp said.

Though most of the prisoners were from the Afrika Korps, there were men from the air corps, paratroopers, infantry, artillery, armored, marines, and even some from occupied countries like Poland. There was even a reported romance between one of the Polish prisoners and an Army nurse. The average age of the enlisted prisoners was 22, with many in their teens. It was the only US camp that housed German general officers. They were "imprisoned" in private bungalows, two generals to each and were allowed one aide between them. One of their complaints was that the communal latrine did not have privacy walls. After much discussion, the commanding officer decided that since the Americans didn't have that luxury, neither should the POWs.

Mississippi writer Willie Morris remembers Sunday afternoon trips to the POW camp. "They were all Afrika Korps troops that were captured in North Africa when Rommel surrendered. This prisoner, standing at the fence, leaned down to try to pet my dog through the fence. In his halting English, he said that my dog reminded him of his in Germany. And then he gave me what was a precious commodity in America in 1942 – especially in Mississippi. He gave me two cans of Pet Evaporated milk that the Swiss Red Cross had given the prisoners. In return, I gave him an equally precious black market WWII commodity: two pieces of bubble gum which I bought in that little store across from the King Edward Hotel."

|

|

|

Even this Landscaping

was allowed by prisoners

|

The tone of the imprisonment was probably set by the first commanding officer, Colonel Charles C Loughlin: "I have for you young solders, no ill will. We will treat you as honorable soldiers if you will behave as honorable soldiers." After that, to his own men, he said "This is my promise, and every man on the reservation must help keep it." His replacement and his officers kept that promise. Other officers were:

Second commanding officer, Lt., Col. James L. McIlhenny

Stockade Commander, Major Harry B. Miller

Capt. G. F. Eigler, Provost Marshal

Lt. Allen N. Connelly, Public Relations

Capt. Winfred J. Tidwell, Adjutant

MP at Gate picture = Hubert Myers

There were four POW camps in Mississippi: Clinton, McCain,

Como and Shelby, also 15 branch camps. More than 20.000 German

prisoners were held in the state.

"The Clinton Camp prisoners have a reunion every year in

Germany. They call themselves the Clinton family."Marion

Rogers Wells, civilian nurse at the camp.

There were, however, escape attempts. Where to, no one really knows. Interviewer: Where did they think they would go? Here they were in Mississippi hundreds of miles from the coast and speaking only German. "All they wanted to do was get out and see the Mississippi and pick some cotton. They had heard so much about it." Wouldn't people spot them and turn them in; after all they had a big PW on their backs? "Oh no, they wore their own uniforms and there were so many uniforms around then, nobody noticed." Marion Rogers Wells, civilian nurse at camp.

This story told by Harold Fonger, the U.S. Army MP on duty: The prisoners tunneled from their barracks in the compound to within 10 feet of the high twin fences surrounding the compound. They had removed tons of dirt without leaving a visible trace. To conceal their efforts, prisoners had sewn cloth bags in their trouser legs, with a draw string at the bottom. Nightly as they tunneled, they would fill their pouches. Next morning while working they would pull the draw strings. Distribute the dirt over fresh ground in their work area where they were clearing land for the subsequent building of the Mississippi basin model. On this particular night when we turned on the lights for the bed check, a German

|

|

|

prisoner was under his blanket wearing his back pack. He was questioned but gave vague answers. He said he was ready to go with the others. A heavy guard was posted and the next day the tunnel was discovered. It ran from the floor of the barracks and almost reached the mesh wire fence.

Karl-Heinze Bohning who now lives in Westfalen, Germany.

Dr. Josef Huber who became a urologist after the war because of

his experience in the POW hospital.

Dr. Gus Jochem, now living in Columbus, GA.

Dietrich Lohbeck

One General did find a way to successfully escape. He, with a little help, sawed through the bars under the camp in a culvert. He escaped, went to town and checked in to the Heidelberg Hotel (where else). He wore his uniform so that no one would notice the PW on the back. Using the hotel stationery, he wrote a scathing letter to the State Department

He then broke back in to the camp and went to sleep. I could find no record of who the general was, but following is a list of the 37 officers that were there. It is believed the lower-ranking officers were at the camp as aides to the generals. In addition to these officers, who lived in private houses on the camp grounds, there were several hundred enlisted men held at the camp as prisoners of war. They were housed in barracks; the foundations of many still remain on the site just south and east of Clinton. The list of officers includes:

General Hans Juergen Von Arnim.

Lt. Gen. Ludwig Cruewell

Lt. Gen. Ferdinand Neuling

Lt. Gen. Hermann B. Ramcke

Lt. Gen. Erwin Vierow

Maj. Gen. Curt Badinski

Maj. Gen. Dietz Von Choltitz

Maj. Gen. Erwin Menny

Maj. Gen. Irwin Rauch

Maj. Gen. Paul Seyffardt

Maj. Gen. Karl Spang

Brig. Gen. Hubertus Von Aulock

Brig. Gen. Detlef Bock Von Wuelfingen

Brig. Gen. Anton DuNCkern

Brig. Gen. Knut Eberding

Brig. Gen. Hermann Heinricb Von Huelsen

Brig. Gen. Carl Koechy

Brig. Gen. Fritz Krause

Brig. Gen. Hans VCon Der Mosel

Brig. Gen. Otto Richter

Brig. Gen. Robert Sattler

Brig. Gen. Ernst Schnarrenberger

Brig. Gen. Hans Georg Schramm

Brig. Gen. Christoph Graf Zu Stolberg

Brig. Gen. Wilhelm Ullersperger

Col. Horst Egersdorff

Col. Alfred Koester

Col. August Viktor Quast

Maj. Anton Sinkel

Capt. Albert Giesecke

Capt. Carl Frederich Krech-Kohnert

Capt. Dr. Ruwisch

1st Lt. Erdmann Von Glasow

1st Lt. Heinz Grosskopf

1st Lt Rolf Lehmeier

2nd Lt. Helmut Fenkel

2nd Lt. Gerhard Runge

Others, it was said, took advantage of the escape route but "they just wanted to go to town to look around and see a movie. In the early evenings there was nothing to do so we just strolled around town to see our friends. I think they just sorta joined in and went back afterwards." said Marion Rogers Wells, civilian nurse at camp.

|

|

|

The following is a reprint from the Jackson, Mississippi Clarion Ledger, 1996

The hospital and the barracks and the projects they worked on are gone today, their time and function lost to the mists of the past. But on this good Friday, in their minds' eyes, twenty German-speaking travelers swept back 50 years, and they could see everything; where they had slept, where they had labored, where they had gone for the nurses and doctors to put them back together.

This was Camp Clinton, a lock-up for German prisoners of war, just off McRaven Road, east of Springridge. In 1943, the Afrika Korps came to town. The Americans here would never be the same. Neither would the Germans. This was where World War 11 stopped and understanding between two cultures took root.

Marion Rogers Wells was a nurse in 1944, 21 years old. Her sister, Katherine, worked at the camp. That's how she heard about the job. "There were two older nurses here at first, the Bass sisters," she says, standing on a gravel road in what used to be the prisoner compound. "They mothered them." Many of the prisoners had not seen home since 1940. Many had been in the desert for three years, with Rommel and Montgomery and Patton, playing push and shove with tanks in the grinding heat and blinding sandstorms of North Africa. "They had malaria and head lice, Wells says. "They were homesick." Many were just kids.

On May 9, 1943, Dietrich Lohbeck, a private, was captured in Tunisia. The Americans came from one direction, the English from another. In between, 80,000 Germans were caught when the vast trap snapped shut. It was Lohbeck's 19th birthday. It wasn't, he says, a bad birthday present. "I was safe. There was no more lead in the air." The Allies had surrounded Josef Huber, a communications specialist in the Luftwaffe, the air force, the day before, on May 8. "For 12 days, we tried to escape. maybe to Morocco," he says. "We'd walk 10-15 miles in the night. In the day, we couldn't do it; the French in Tunisia were against us. Hitler, Huber says, had won over Berber tribes by promising their own government and getting rid of the French. So at night, Huber and his friends traveled from one Berber campsite to another, listening for the telltale barking of the Berbers' dogs. After nearly two weeks, they realized it was hopeless. "We knew the English were friendly," he says. Americans were a great unknown. So they tried to surrender to an English lieutenant. But he handed them over to a couple of American GIs. "We were," Huber says, "happy to be out of the fight." Many of the prisoners were moved through the Mediterranean Sea to Gibraltar and on to Scotland, where they spent six weeks. They sailed to New York, went straight to Penn Station and were placed on trains bound for a place called "Mississippi". Josef Huber had medical school on his mind when he was growing up in Munich, in the Bavarian mountains. But Hitler's Case White, the invasion of Poland, swept him out of his life and into the swirling vortex of world war. It took capture and Camp Clinton to put him back on track. "We got good treatment," he says. "Marion can tell you. We worked together for a year. l was a surgical technician." After a year of working on Germans, Marion Rogers Wells Wells and a couple of her friends enlisted in the Army so they could put Americans back together. Her friendship with and affection for Huber, however, has spanned five decades. Fifty years ago, in 1946, the prisoners were trucked out of Camp Clinton and sent either to Great Britain or France, where they spent another year before being mustered back into civilian life. Huber went to medical school and became a neurologist. A slim, fit man, he has been retired from his 30-year practice for 10 years now. He climbs mountains in his native Bavaria, plays the violin in an orchestra. and takes philosophy courses at the University of Bavaria.

Marion Rogers Wells has never spent a working day away from veterans. After the war and the Army, she went to work for the Veterans Administration. She's retired from the Jackson Veterans Affairs Medical Center, serves as the relief nurse in the infirmary at Mississippi College and focuses her energies on Clinton and its history. "Whenever former prisoners have come back," she says, "I've tried to show them around. l never was afraid of them. We never treated them like the enemy." They were just somebody else's sons from. the other side of the Atlantic, caught by the whirlwind of history, by events of unimaginable vastness and terror. At Camp Clinton, they found an oasis of peace beyond Hitler's jack-boot and the bombs of the Allies.

War is hell, and it's hell to clean up. When Franz Prager got back home, hardly any of home was left. He grew up in Essen, in Germany's industrial heart. Allied bombers, trying to knock out the vast Krupp works, had reduced Essen to rubble. "It was very shocking," he says. At Camp Clinton, Prager had worked for a builder named Monroe G. Landrum, his foreman. And he had paid attention. "My hometown was 65 percent destroyed. And so there was a lot of work for bricklayers and builders." In great disaster, often there is great opportunity. Prager took advantage.

Lohbeck, captured so young, grew up in Westphalia, near Holland. Twenty years ago, on doctor's orders for the treatment of asthma, he and his family moved up to the mountains of Bavaria. Three years ago, at age 70, he sold his accounting firm and retired. He has made five trips to the United States, four times to the Jackson-Clinton area. He even, on a lark, got a Florida driver's license. On this Friday, standing where the prison compound used to be, he pulls out his wallet and shows me a driver's license from 1940. "The picture," he says, "was replaced in 1952." That was because in the 1940 photo he was wearing the uniform of the Hitler Youth. "I've never met anyone in the United States who has not been helpful and friendly," he says. A relative of the family he and his wife are staying with in Florence owns an air conditioning firm. He handed Lohbeck 50 business cards and asked him to hand them out to the visiting Germans. "'They are elderly,' he told me," Lohbeck says, " 'and they are in an unfamiliar place. If they need to, they can call that number and one of my people will come get them.' "Isn't that wonderful?"

Lohbeck looks across the long expanse of green where so many of his countrymen spent three years so long ago under such very different circumstances. "We used to be enemies, we used to fight each other," he says quietly, "and we're crying when we have to leave each other now."

Over 50 years ago, German prisoners planted bulbs in Mississippi soil. Down at the front gate of this place where peace and understanding took root so long ago, those yellow tulips still sway in the April breeze.

|

|

|

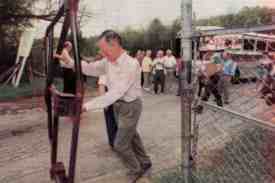

"l never thought l would return," said 67-year old Erich Becker, fighting back tears, pointed to the spot where his barracks stood some 47 years ago. He came to Clinton's prisoner of war camp in August of 1943 and remained at the 790 acre facility southwest of the city for three years and then was assigned to Foster General Hospital in Jackson for six months before the end of World War II.

While visiting Clinton last week, be was the guest of Marian Rogers Wells. When they first met she was a civilian nurse at the camp. "l remember her from the camp and from the hospital," Becker said. Well later joined the Army as a nurse with the rank of lieutenant. . She arraigned for Becker and members of his family to visit the old camp area north of McRaven Road The property now belongs to Mississippi College. Wells handed him the key so he could open the front gate to the property. "l want to do this now that l have come back as a free man," Becker said. Although be was an electrician and a communications specialist in the Germany army he told American POW officials that he was a cook. "l thought l would get to eat better that way," be explained. "l watched the black women cook and learned from them. I think l was a good cook," he added. His nephew, Wili Klappert of Hickory, N. C., translated when necessary.

"One of the women, her name was Ann, wrote to me after the war but she didn't give me an address," Becker said. "l want my name and address to be included in this newspaper. l would like to hear from anyone who had anything to do with the camp or who was at the hospital," he said. Becker's home address is: Erich Becker, Eichenen Strabe 62, 5910 Kreuztal-Eichen, Germany. In a letter he got from Ann, the names of Willie B. Lucy, Ida B. and Easter were mentioned.

Becker arrived in the early days of the camp and his first job was to help clear trees near the fences. He then worked on a farm for a short time. "l enjoyed being here. We were treated decently. The tables were set, we had warm water and decent clothes," Becker said. A visitor to the camp in late 1943 described the POWs as "suntanned and making the best of their situation."

The prisoners were governed and disciplined by their. own chosen leaders, and when they went outside the compound on official assignments, they were guarded by American soldiers. POWs wore blue prison uniforms emblazoned with an orange PW. They were paid 80 cents per day for their labor. Despite their confinement, prisoners had many privileges. Their food was the same as was given American troops; and their housing was comparable to Army barracks. General officers lived in bungalows and were not required to work. POWs organized musical groups, some had bobbles and many particlpated in a variety of recreational activities. . Becker tecalls one unusual incident in connection with a recreational facility at the camp. "There, was a football (soccer) field near 'my barracks, and it had fights around it. One night we beard a loud noise and looks up and a pilot in a small plane bad landed on the field. Perhaps he thought it was an airport," Becker said.

Becker showed his wife and cousin various parts of the camp as they look pictures and chatted in German and English. Wells and Becker were able to recall the locations; of many of the buildings at the camp. Herbert and Edith Klappert, Willi Klappert's brother and sister-in-law were also along for the tour. Becker, who was captured in North Africa, considered himself a professional soldier. When the end was near for the Germans in North Africa, Becker and three other soldiers deserted, planning to make their way to Spanish Morocco, some 1,200 miles away. "En route we came upon an American vearnp and decided to try to steal, a jeep. We were crawling around under the vehicle when a Arab saw us and turned us in to the American soldiers," Becker said. "So we became. a part of the 15,000 POWs that were captured," he said." More than 1,000 men of Field Marshal Rommel's elite Afrika Korps were brought to the camp where many were put to work preparing a model of the U.S. States and the Mississippi River.

Before they left, Becker said he wanted to see the Mississippi River, Wells took them to lunch at Delta Point in Vicksburg. One of the events of World War II still disturbs Becker. "We didn't know what was happening to the Jews in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. It was a wry bad thing," he said.

After the war he married his fiancé, Gertrud, and set up an electrical contracting shop. He retired two ago and let his son take over. "But "l still have some connect with the business. It helps keep me young," he said They had a wonderful time and l did too. I'm glad It worked out the way It did," Wells said.

"After the camp was closed, the area sat vacant for a while. Then in the spring of 1946, construction was begun on a $250,000 new office and laboratory building and by late summer, it was in operation. The Concrete Division made use of many of the camp's vacant structures. In the late fall of 1969, the Concrete Division was moved to Vicksburg where an ultra-modern facility had just been completed. Two years later, in October 1971, the old camp site used by the Concrete Laboratory was declared surplus. By this time, the administration and operation of the Mississippi River Basin Model had been moved to a nearby facility and all but a small number of the buildings original to the camp dismantled. It was announced that state and local governments and non-profit institutions would be allowed to make application to acquire the property. Among those who expressed an interest was Mississippi College, located in Clinton." After an extended period of negotiations between the government and the school, the two parties reached an agreement on the transfer of the land.

On April 20, 1973, at a special ceremony at the Waterways Experiment Station, the deed to 220 acres was presented to Dr. Lewis Nobles, president of Mississippi College. According to school officials, the greatest portion of the property was to be used for field research in biology, botany, and chemistry and as a center for physical education and recreation. Conference and administrative facilities and a driver education course were also planned."

Most of the proposed programs, however, were never put into effect. A recreation center was set up in one of the abandoned WES warehouses, but it was used for only a short time and no longer stands. Apart from an occasional field trip to the area, no study facilities were ever built. The only regular use of the property has been for cross-country track events. Presently, much of the site is overgrown: and except for some of the old crumbling streets and a few foundations, there is little evidence that a 3,000-man prisoner of war camp was ever there."*

*The last three paragraphs and, indeed, many of

the facts (the accurate ones) about

Camp Clinton are from a master's thesis on Camp Clinton by Michael

Allard!

Michael is currently putting it in a book. We'll let you know

when it's published.

|

Visitors since

June 6, 2000 |