|

MARKET GARDEN

by Aubrey L. Ross

Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Retired

|

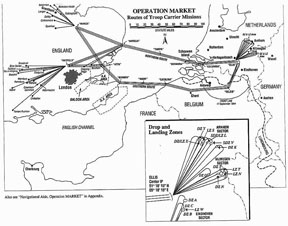

Click image for a larger view RECOMMENDED!

It will open in another window so you can keep it open while reading.

Click image for a larger view RECOMMENDED!

It will open in another window so you can keep it open while reading.

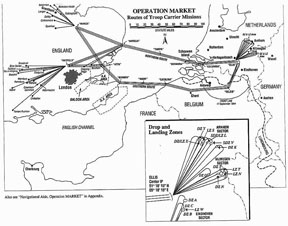

Map of routes and

zones |

| Editor's Note: After

the initial, and slightly surprising, success of the landings at

Normandy, the Allies hoped for a steady push across France –

maybe even home by Christmas. What, sadly, happened was that the

Allies bogged down in a virtual stalemate. In August, British Field

Marshal Bernard Montgomery pushed hard for what a later American

general would call a "Hail Mary." He wanted to make an

end-run around the battle through northern France, the low countries,

and into the industrial heartland of Germany, the Ruhr. The largest

airborne drop in history (to that date) was made to capture and

hold three strategic and a few smaller bridges until the mass of

land forces could arrive. All went well except for a minor little

detail lost to Allied intelligence . . . the II SS Panzer Corps.

Here is the story from one who was there! |

|

In

early September 1944, a decision was made by Supreme Allied Headquarters

to drop an airborne force in Holland. The objective of this ill

conceived debacle was to capture several key bridges, one crossing

the Rhine river near Arnhem, and hold them for the advancing troops

that were inching slowly toward Germany. This operation was code

named MARKET GARDEN, and was not canceled, as many of us would

wish later. The book A Bridge Too Far tells this story far better

than any that I have read. Our mission in Operation MARKET was

to transport airborne forces to the Arnhem-Nijmegan area of Holland.

Once on the ground, these forces were to seize and hold vital

bridges until relieved by the British Second Army driving north

through Eindhoven. The routes to the drop zones were planned so

as to avoid most of the heavy antiaircraft fire. However, it was

known that both heavy and light antiaircraft guns were in the

Arnhem and Nijmegan areas and at the landfall point at Schouwen

Island.

|

|

|

|

We did not do any specific

training for this mission nor was there a dress rehearsal. We

were very happy to learn once again that our group would not have

to tow gliders on this mission. This chore fell to one of the

less fortunate groups.

No Troop Carrier pilot ever wanted to tow gliders especially into

combat. A normal cruise speed for the C-47 was 145 to 155 MPH,

but with a glider you would be slowed to 90 to 95 MPH with increased

power. It was also much more work for a pilot when a glider was

in tow with airspeed hovering near stalling speed.

|

|

On

September 14, 1944, we, once again, had "Guests" move

onto our base, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 82nd

Airborne Division. At the first mission briefing, we learned that

the 315th's first destination was Drop Zone "O," located

about three miles southwest of Nijmegan and one-half mile north

of the Maas River. Two serials of 45 aircraft each were to be

used to transport 1240 paratroopers and 473 parapacks. Our route

to the target was to the east coast of England at Aldeburg, then

94 miles across the North Sea to Schouwen Island in Holland. From

Schouwen Island, it was approximately 90 miles to the drop area.

On the morning of the first MARKET mission, hundreds of Allied

bombers and fighters dropped more than 3000 tons of fragmentation

bombs on the suspected antiaircraft sites along the troop carrier

route.

|

|

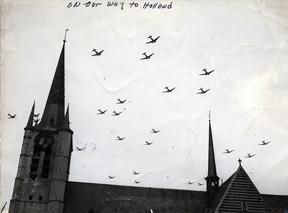

Click image for a larger

view

310 Sqd. C-47 Over England 1944

|

On

Sunday, September 17, 1944, at 1039 hours, 90 aircraft began taking

off from Spanhoe Airfield loaded with members of the 504th (PIR),

82nd Airborne Division, bound for Holland on a mission that was

designed to shorten the war. The first serial of 45 planes was

led by Lt. Col. Dekin and the second was led by Lt. Col. Gibbons.

We formed the usual V of V's formation and joined a stream of

troop carrier traffic moving toward the coast of Holland. Shortly

after passing the Dutch coast, we encountered fire from antiaircraft

batteries along our route. Just past the coast, the 34th Squadron's

C-47 no.308, piloted by Captain R. E. Bohannan, was hit by flack.

The left engine and one of the underslung parapacks (parapacks

are large cylinders containing supplies slung under the belly

of the airplane) began to burn and he went down near Postbahn

van den Stadscherdike at Fifnaart. The crew chief along with 15

paratroopers parachuted to safety, but they were soon captured

by the Germans. Most of these men were wounded. Capt. Bohannan,

Lieutenants. Felber and Martinson, and S/Sgt Epperson were killed.

In a rare quiet moment, my copilot doing

the flying, I stared out the windscreen and reflected . . .

|

Flashback to May 1943

Click image for a larger view

One of our C-47s

Over Clouds |

It was May 28, 1943, one

of the happiest days of my life for I had successfully completed

pilot training satisfying a dream from early childhood and also

receiving a commission as a second lieutenant in Army Air Forces.

My euphoria was short lived when I saw my assignment orders were

not for a fighter squadron but read for Troop Carrier command which

I had never heard of . . . I knew that the needs of the service

come first so I was on my way to Bergstrom Air Base in Austin, TX.

Here we trained in the military version of the twin engine Douglas

DC-3, the mainstay of most airlines during the 1930s and 1940s.

The military made some modifications and designated it the C-47

(affectionately known as the "Gooney |

| Bird")

but it was still a slow, unarmed transport with no armor plate nor

self-sealing fuel tanks. This was the airplane used by Troop Carrier

during the war. We did receive, during the summer

of 1944, a few of the new Curtis C-46 aircraft which was faster

and |

|

|

carried a larger

load. Also about the same time 2 B-24 Liberator bombers

with all armaments removed and replaced with fuel tanks were

received by each squadron. This airplane was designated the C-109

and was used primarily to supply Patton's army with gasoline during

his dash through Europe. This was a flying gas tank as it was capable

of carrying more than 2900 gallons of gasoline. Crews on the C-109

didn't carry matches or cigarette lighters or anything that might

ignite the gasoline fumes. |

|

| There

were also a large number of Waco CG-4A gliders in the Troop Carrier

inventory. After a few hours of

training in the C-47, I received orders for overseas. I departed

in September 1943 with an inexperienced crew bound for North Africa

flying the C-47 |

Click image for a larger view

Spanhoe C-109 Tanker In Our Squadron |

across the North Atlantic

route. We left the US from Presque Isle, Maine. From there on to

Goose Bay Labrador, then to Greenland, next to Iceland, then on

to Scotland, then Southern England where we leaped off for Casablanca.

From there I went to my assignment in Sicily with the 62nd Troop

Carrier group. We hauled freight, carried passengers (some VIPs

such as Churchill), evacuated wounded from the front as well as

dropping paratroops when the need arose. We also flew supplies into

Yugoslavia, Albania and Greece to Tito's troops who were giving

the Germans a hard time in the Balkans.

In March 1944, volunteers were sought to

transfer to England to train for

the invasion of Europe, I was one of the

first to volunteer because our living conditions |

were so bad and I knew things had to be better

in the England. Upon arrival in the United Kingdom, I became a member

of the 310th Troop Carrier squadron, in 315th Troop Carrier group at Spanhoe

airdrome about 80 miles north of London. Several missions were flown dropping

paratroops on D-Day without significant losses, but it a different story

in operation MARKET GARDEN as follows.

Back to being shot at

The ground fire increased as we neared the

drop zone and seven of our aircraft were hit before we reached the drop

zone even though fighters were keeping the pressure on the gun batteries

all the time. Most of the planes dropped their troops on or near the

drop zone. As soon as the last man cleared the plane, we would dive

to the deck to provide a lesser target and avoid the heavy ground fire.

|

On

D-Day plus one, September 18, 1944, two serials of 27 planes each

left Spanhoe to drop the troops of the British 4th Parachute Brigade

on Drop Zone "Y," northwest of Arnhem. On this day,

eleven aircraft were damaged and two were shot down before reaching

the drop zone. Lt. Tucker's plane (34th Squadron) was hit and

began burning 16 miles short of the target. All bailed out and

four days later Tucker and his crew of Lt. D. O. Snowden, T/Sgt.

W. W. Durbin, and S/Sgt. W. E. Hewett, returned having evaded

capture. The paratroopers landed near Bennekon, Holland. Lt. Spurrier's

plane, flying on the right wing of 43rd Squadron Commander, Lt.

Col. Peterson, began burning near Herrogenlosch. We later learned

that when the crew chief, Cpl. Russell Smith saw

|

|

Click image for a

larger view

Spanhoe 1944 Preparing for Drop |

the fire inside the front

of the aircraft and when he received no response from the pilot's

compartment on the intercom, he ordered the troops to jump and he

and the radio operator followed, jumping at a very low altitude.

They all landed near Opheusden, between the Waal and Rhine rivers.

Lt. Spurrier was unconscious and unable to jump so Lt. Edward Fulmer,

the copilot, saw an open field, and crash landed the airplane in

an attempt to save Lt Spurrier. The plan's wing struck a power line

tower, slid along the ground, and exploded in flames. Lt. Fulmer

was able to escape through a side window. Lt. Spurrier and Cpl.

Hollis, radio operator, died of their injuries. Cpl. Smith was hidden

by the Dutch underground for several weeks and was later turned

over to an American unit. He was immediately sent back to the U.

S. because the policy was to transfer any airman who had come in

contact with the underground to another theater. |

|

I

experienced a close call while dropping those British troops at

Arnhem on September 18. I was leading a flight. There were two

planes flying formation with me, one on each wing. As we approached

the drop zone, we encountered heavy ground fire. Looking out either

side of the plane you could see large black explosions, some seemed

just inches from the wings of the airplane. As I began dropping

the paratroopers, a shell came through the open door (the rear

door was removed for drops) and hit one of the British paratroopers

seriously injuring his left arm. The crew chief pulled him aside

and all of the others jumped. As normal procedure, just as soon

as all troops had cleared the plane, I dove for the deck to make

us a more difficult target for the Germans. About this time the

crew chief informed me that we had a wounded paratrooper in the

back. I sent my copilot back to the rear of the airplane to administer

first aid. He came back a short time later and, said that he couldn't

do anything; the sight of blood made him sick. I was

|

|

very upset and angry with him. After a few of

my favorite curse words, I asked him sarcastically if he thought he could

fly the airplane for a short time without getting sick. I gave the controls

over telling him what heading and altitude to maintain, and I went

|

|

back to see if I could

aid the injured man. This was the first opportunity I had to practice

the first aid training given us in school. The poor guy was in

shock, with his left arm hanging by a thin piece of skin almost

completely severed at the elbow, and blood was squirting out of

the blood vessels. With the help of other crew members, I tied

a tourniquet around the upper arm to slow the bleeding, administered

a shot of Novocain, bandaged to keep the arm together, treated

him for shock, then went back to the cockpit and headed for home

on the most direct route. I wish I had followed up on the outcome

of this trooper's treatment, because it appeared to me that he

would lose his arm. Our airplane was only hit by this one shell

that entered through the open door.

The 315th was not scheduled on September, 19, and all Troop Carrier

Wing missions were canceled because of poor flying weather. We

did fly on D plus 4

|

even though the weather was very marginal with

visibility down to less than two miles and cloud layers from 200 feet

to 9000 feet. The precarious position of the British troops engaged in

a fierce battle at Arnhem dictated the urgency of this mission. The troops

to be airlifted were those of the Polish Parachute Brigade.

|

The

first serial of 27 aircraft left Spanhoe at 1310 hours. Because

of limited visibility, instructions were issued to assemble at

1500 feet, an altitude above the haze layer. This serial was composed

of planes from the 43rd and 34th squadrons. The planes were never

able to form so all but two returned to the base. Two pilots broke

into the clear and tacked into a formation from the 314th group

Troop Carrier Group.

The second 27 planes from the 309th and 310th squadrons (The 310th

was the squadron to which I was assigned), led by Lt. Col. Stark

began taking off from Spanhoe at 1427 hours. Two planes from this

serial came back because of weather while the rest of us climbed

through the overcast to above 10,000 feet, where we were able

to assemble above the clouds. Looking back now I am

|

|

amazed that we didn't have more midair collisions

than we did with that many airplanes climbing through the overcast to

form on top. The formation remained at this altitude until over the Belgian

coast where the clouds began to thin, and a gradual let down was begun.

We descended to 1500 feet and made our way to Driel, some two miles southwest

of Arnhem. The drop zone was reached at 1700 hours and we encountered

considerable flak and a number of airplanes were hit, but, in spite of

the flak, all planes dropped their loads of Polish troopers. The heavily

burdened Polish troops took longer to clear the airplanes than was estimated.

This

|

|

prevented the formation from

turning as soon as planned, and as a result, when we did complete

our turn, we were over the town of Elst and severe flak. As usual,

we dove to get as close to the ground as possible to avoid the German

flak. Five airplanes were shot down and several others landed at

nearby air strips because of severe damage.

Lt. Col. Stark was hit in the chest by

shell fragments. He felt certain that the flak vest he was wearing

saved his life. A friend and fellow pilot of mine from the 310th,

Lt. Kenneth Wakley was shot down in plane number 612. Lt. Bruce

Borth, copilot, Lt. M. C. Beerman, navigator, T/Sgt. Magnus, crew

chief, and S/Sgt. Carl Javorsky, radio operator, were killed as

well as Lt. Wakely.

Approaching the DZ, another 310th pilot

and friend, Lt. Cecil Dawkins, was |

wounded in the face and head when his plane took

two flak bursts. With one of the fuel

tanks in port wing burning and flames sweeping down the left side of the

fuselage, Lt. Dawkins moved his plane out of formation, dropped his troops,

and then ordered his crew to bail out. Lt. Cleon Worley (Moose), one of

my roommates, was flying copilot on this mission with Dawkins (At the

last

|

minute

the regular copilot became ill), so Moose volunteered to go in

his place. Lt. Worley, (Moose as all of us called him) was an

old timer having come up with the group of us from Italy and had

been a first pilot and flight leader for some time, so it was

most unusual for him to be a copilot. Moose along with Lt. J.

R. Wilson, navigator, S/Sgt. W. O. White, crew chief, and S/Sgt.

J. Ludwig landed safely and made their escape with the assistance

of the Dutch civilians. None of these crew members ever saw Lt.

Dawkins leave the stricken aircraft, and everybody assumed that

he had died when the airplane crashed.

Several years after the war, in a letter

to a friend, Dawkins provided information about his experience.

He recalled that after he gave the order for the crew to bail

out and as he was attempting to leave his seat, there was an explosion

under the cockpit floor. When he regained consciousness, he was

aware of being on the back of a German tank rolling down a blacktop

road. At the first aid station where

|

|

his wounds were being attended, a German nurse

who spoke English told him that a German tank crew pulled him from the

river after his plane exploded and they saw him thrown into the water

with no parachute. He was interrogated for several days, then sent to

Stalag Luft One (Prisoner-of-War Camp) on the Baltic Sea. After two weeks

in the camp, Dawkins and two others attempted to escape, one was caught

by guard dogs, one was shot and killed, and only Dawkins was successful.

He made contact with advancing Russians, where he stayed until a British

unit was encountered during the last days of the war. I would think that

Dawkins used up a lot of his luck on this mission. He was later awarded

the Distinguished Service Cross by his country and the Order of the Bronze

Lion by the Queen of the Netherlands.

Lt. Worley (Moose), Lt.

Wilson, Sergeants, White and Ludwig, were back at Spanhoe in just a

few days after they bailed out. They had been walking along a canal

when they met a Dutch farmer carrying a machine gun walking behind a

German Soldier who had surrendered. The Dutch farmer handed the weapon

to Moose and wanted him to take charge of the prisoner. They were all

taken to a member of the underground who made arrangements for them

to be escorted to British-American lines. Soon after they were flown

back to England to join their unit. They were debriefed and sent home

to the states in a matter of a few days, because it was a policy to

transfer people who had been shot down and escaped through the underground

to another theater. This was done to protect members of the underground

because if an escapee fell into the enemy hands, they might be made

to tell what he knew about the underground.

Click image for a larger view

Near Munich May 1945 Carrying Ex POWs |

Moose was flying back to

the States on one of the scheduled transports which meant that he

was limited to the amount of baggage he could carry, and also he

would not be allowed to bring back the German machine gun that was

taken from the prisoner. As a result I became the new owner of a

gun that was known as a "Burp" gun. It was nicknamed "burp"

because it would spit out about twenty rounds so fast that it sounded

like one big burp. I was able to bring this machine gun home with

me because I flew my own airplane back and customs were very kind

to us. It was illegal to own such an automatic weapon unless it

had been rendered inoperative in some manner. I traded the gun to

Dr. Walter Borg, a close friend of mine in San Antonio in 1955 when

I was transferred to the far east.

Another 310th plane piloted by Lt. Jacob Boon was struck by enemy

fire after the Polish jumped and later crashed in the drop area.

The copilot, crew chief, and |

radio operator were all wounded, but Lt. Boon

was able to crash land and get all of them out before the plane exploded.

For this heroic act he was awarded the Silver Star,

Our squadron commander,

Lt. Col. Hamby, landed at Brussels with a severely damaged aircraft

rudder and two wounded men aboard Sergeants. Harold and Combetty. A

count of holes in the airplane totaled 150.

Lt. O. J. Smith, 310th

squadron, had his crew chief, Cpl Doan and radio operator Sgt. James

wounded and bleeding profusely, so he sat down at Eindhoven to get immediate

medical attention for them. This aircraft had a damaged rudder control

and a total of 600 holes were counted.

Captain F. K. Stephenson's

plane was riddled by flak and was burning as he skillfully crashed landed

in a wooded area. Stephenson, along with his 309th crew of Lt. Garber,

Lt. Arnold, T/Sgt. Berotti, and S/Sgt. Maxwell, escaped serious injury.

C-47 no. 6132, another 309th plane, crewed by Lt. Biggs, Lt. Pearce,

Lt. Yenner, T/Sgt. Abendschoen, and S/Sgt. Herbst, burst into flames

when hit by flak and exploded as it crashed into the ground near Elst.

All were killed.

A 43rd Squadron C-47,

piloted by Lt. Cook received several hits while returning along the

Brussels corridor. He lost all hydraulic pressure and most of his fuel,

so he made an emergency landing at one of the Brussels airports. He

narrowly missed crashing into several parked airplanes and finally came

to rest against a hangar. The entire crew escaped uninjured

Click image for a larger view

Our Quarters Amiens France April 1945 |

I was lucky again, no serious

hits to my airplane. There were a lot of empty beds in the quarters

at Spanhoe that night. We would wait a while hoping for some good

news before we packed and stored their personnel belongings. This

was a very sad thing that we had to do from time to time, and worse

were the letters that the chaplain and squadron commander had to

write to the families. There were only three of us in the room now,

my good friends Terry Colwell, Jason Rawls, and myself.

On D+six, Sept. 23, Lt. Col. Peterson,

43rd squadron commander, led 41 aircraft to transport the 560 Polish

paratroopers and 219 parapacks that did not reach their objective

on D+four. They arrived over the drop zone "O" at 1643

hours and experienced very little ground fire. All planes returned

without damage.

|

A few days after the initial assault, a good

grass landing field had been located two miles west of the town of Grave.

With obstacles around the field removed, there were 4200 feet of usable

landing area.

The 315th sent 72 planes led by Lt. Col Lyons to transport an antiaircraft

battery and units of a Forward Delivery Airfield Group. In addition

to men, the cargo consisted of jeeps, trailers, antiaircraft guns, ammunition,

rations, gasoline, and motorcycles. We took off from Spanhoe at 1130

hours and were escorted by Mustangs and Spitfires all of the time we

were over the continent. No enemy planes got through to strike the congested

landing area. We were told that several German fighters tried to intercept

us but were shot down by our escort.

Click image for a larger view

Bore, France Near Amiens April 1945 |

After landing, the transports

were unloaded and sent off as rapidly as possible to make way for

succeeding serials to land. Two hundred and nine C-47s landed at

Grave between 1350 and 1740 hours and brought in 657,995 pounds

of combat equipment plus 882 men. Occasional ground fire was encountered

on approaches and return routes, but no 315th airplanes failed to

return from this airborne landing mission. As soon as an airplane

landed, all crew members regardless of rank jumped in to assist

with the unloading for nobody wanted to be on the ground any longer

than necessary.

The constant pressure of the German forces caused the Arnhem position

to be abandoned by the British on the night of September 25. An

estimated 1130 British and Polish Airborne troops were killed on

operation MARKET GARDEN and another 6200 were captured. |

Approximately 3500 men from the American 82nd and 101st

Divisions were listed as killed, wounded, or missing. All objectives

but the bridge at Arnhem had been achieved, but without that key bridge

over the Rhine river, the operation had failed. All troops, both Airborne

and Troop Carrier had done all they could do, but in the end, it was

not enough. Who was to blame for this failed mission was anybody's guess.

I suspect that there was enough blame to go around and then some. The

flying, the fighting, the dying was mostly done by the very young, 18

to 25 year old men who just obeyed orders from their superiors without

question. Wars must be fought by the young who are immature, naive,

and adventuresome.

The rest of Quesada's Crashed P-38 story

(below right)

November 1, 1958 Elwood Quesada took oath

as

November 1, 1958 Elwood Quesada took oath

as

FAA first Administrator |

In 1958 Jet travel was upon us. A severe

midair collision over the Grand Canyon in 1956 spurred congress

to pass the Federal Aviation Act created the FAA as an independent

administration. National Airlines using a B-707 leased from Pan

American flew the first New York to Miami jet passenger flight,

The Federal Aviation Agency became the Federal Aviation Administration.

General Quesada became it's first administrator - the P-38 wasn't

mentioned in the ceremony.

|

|

More images

Click image for a

larger view

Larry Bassett Jr., Aubrey Ross (the author) and Terry Colwell |

|

|

| |

|

The C-47 in the background is the remains of

an airplane that was damaged very badly when it was being loaded

for the D-Day drop. A paratrooper dropped a hand grenade as he

climbed aboard killing several troops and injuring several others.

The troops that were not injured climbed aboard other aircraft

and made the drop. The airplane was so badly damaged that it declared

a total loss and the fuselage you see in the picture was used

for ditching practice.

|

Photographs by Aubrey Ross

|

More

or Market Garden right here in Kilroy Was Here:

The Sergeant Who Captured

a Division ....... Click

Here

The largest airborne operation in history?

(a quiz) ........ Click

Here

Operation Market Garden (Dutch site

translated) ........

Click

Here

PFC Joe

Mann (Medal of Honor winner at Market Garden)........Click

Here

Hall of Heroes (PFC Alfred Nigl) Glider

unit at Market Garden) ........

Click

Here

Kilroy is Here at C-47 that was there

too and still flying........

Click

Here

|

Send Corrections, additions,

and input to:

WebMaster/Editor

Click

the star for

Site Map  .. ..

|

|